Chapter 22: Fabvier and the Fighting Fiends of Nafpaktos

Chapter 22: Fabvier and the Fighting Fiends of Nafpaktos

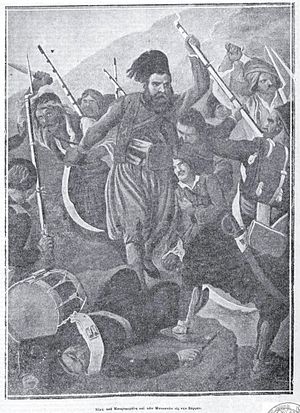

The Greeks Assemble outside Nafpaktos

The fall of Missolonghi was met with muted celebration across the Ottoman Empire, with the loudest cheers of jubilation coming from Topkapi Palace in Constantinople. The infernal city had finally fallen to the Sultan’s armies, and there was no one more thrilled at the result than Sultan Mahmud II himself. By his command, the minarets throughout the city proclaimed the glories of Allah and the victories of his servants over the traitorous Greeks. Surprisingly, the least enthused about Missolonghi’s capture were the Ottoman soldiers themselves. Rumors spread across the empire, that it was the Egyptians and not the Turks who were responsible for the victory over the Greeks and rather than boosting their morale, it only fell further as a result.

The yearlong undertaking needed to take the city had been great, of the 50,000 Albanian, Egyptian, and Turkish soldiers sent against the Greeks in the lagoon and in the city, over 18,000 had died, with as many men succumbing to illness as those who succumbed to Greek bullets or blades. Another 15,000 had been so badly mauled in the fighting or made to suffer from other maladies that they were rendered unfit for further combat against the Greeks, with most being mustered out of service entirely or relegated to garrison duty. Over the next month following the capitulation of Missolonghi, their numbers were reduced further still. His obligation fulfilled, Ibrahim and his remaining 4,500 men, many of which were wounded, departed for the Morea to complete his conquests there. Another 2,000 were called away to the East to aid in the last push against the Greeks of Atalanti and Salona. The Greeks who had escaped from Missolonghi also continued to prey upon the Ottomans when they ventured too far from their camps, killing or wounding an additional 2,300 Albanians and Turks between the beginning of May and the end of July.

Command of the army was also an issue for the Ottomans. The death of Resid Mehmet Pasha in January had left the Ottoman troops effectively under the command of Ibrahim Pasha, but his departure soon after the siege’s conclusion in early May had now left them without a clear leader once again. The only other Ottoman commanders of any significance present at Missolonghi were the Kapudan Pasha, Khosref Pasha and Yusuf Sezeris, the Pasha of Euboea. Both men, however, refused to concede leadership to the other and as a result they did little more than argue for the next two months before Khosref Pasha was finally recalled to Constantinople in early July. Now alone, Yusuf Pasha set about installing garrisons in Missolonghi and its environs before he acted on orders of his own, the reconquest of Nafpaktos. The city and castle had fallen to the Greeks right from underneath Yusuf over two years ago, now was the chance for him to regain his lost honor.

Reaching Nafpaktos on the 24th of July, with 6,000 infantrymen and 500 cavalrymen, he found the city and its castle lightly defended by no more than 900 Greeks in total, many of whom were likely townsfolk who had been levied for the defense of their city. His good fortune quickly ran out, however. While he could establish siege works along the western edge of the city, his efforts to the North and East were met with great resistance from the Greeks of Nafpaktos. Reinforcement by sea also proved to be an aggravating problem for the Ottomans as the Egyptian fleet had departed with Ibrahim, and much of the Ottoman Navy had left with Khosref Pasha leaving Yusuf with little more than 3 sloops, 2 brigs, and several smaller vessels to maintain a porous blockade around Nafpaktos. While the Ottomans held the Gulf of Patras, the Gulf of Corinth lay entirely in Greek hands, enabling them to quickly rush men and supplies into the city at a moment’s notice. One of those men was the French Philhellene Charles Fabvier.

Colonel Charles Nicolas Fabvier, French Officer and Philhellene

Colonel Charles Nicholas Fabvier had served as an artillery officer and engineer in the armies of France during the Napoleonic wars. Fabvier had an illustrious military career under Napoleon serving with distinction in the Ulm Campaign, Russian Campaign, the Hundred Days Campaign and as a part of various diplomatic missions to the Ottoman Empire and Persia. His career was derailed by injuries which limited his time in the field of battle where he could gain glory or élan. Fabvier continued his service to France after the restoration of the Bourbon Monarchy in 1815 but due to his strong association with the Revolution he was relegated to a minor role. After being charged with a crime he did not commit and repeatedly subjected to ridicule over his liberal beliefs, he was finally pushed out of the French Army entirely in 1823. With nowhere else to turn, he and a group of other French and Italian Bonapartists embarked on a ship bound for Greece to make a new beginning for themselves in Hellas.

Arriving at Navarino in the Summer of 1824, Charles Fabvier intended to establish an agricultural and industrial colony with his fellow expatriates in Greece, but the needs of the Revolutionary Government compelled him to act in its defense.[1] Barely a month after arriving in Greece, Fabvier left for Britain to lobby additional support for the Greeks in London, where he raised funds and gathered volunteers to serve in Greece. After spending a year in Britain, he returned to Nafplion in mid-June of 1825, just in time for Ibrahim Pasha’s attack on the city. Fighting alongside Yannis Makriyannis in the battle of Lerna, Fabvier fought heroically alongside the Greeks earning their trust and comradery. For his valor, the Government, appointed him command of the 2nd Regiment of the Hellenic Army which was presently in Southern Roumeli outside Salona. The move also put him under the command of Odysseus Androutsos, the recently appointed Governor General of Eastern Roumeli.

Androutsos had made amends with the Government in Nafplion over the Summer and Fall of 1824, due in large part to Byron’s payment of his arrears. Trewlany and Stanhope had both insisted upon Byron to finance their benefactor Androutsos, and while he was nowhere near as devoted to the man as his companions were, Byron recognized the importance of retaining the services of this talented man for the Greeks. Using his position as the custodian of the first English loan, Byron had the Nafplion Government pay Androutsos and their men for their services and bestowed upon them new weapons and fresh munitions. The apparent show of support galvanized Androutsos, as his vigor had been waning in the months following the disappointment that was the Congress of Salona, and compelled him to act. The news of his hated rival Ioannis Kolettis’ withdrawal from the Executive following his grievous injury at the hands of Charalamvis in January also pleased the klepht and did much to reconcile him with the Nafplion Government. [2]

Together with his deputy Yannis Gouras, Androutsos moved North from Athens to fight off the Ottoman offensives towards Atalanti, Livadeia, and Salona for which he was named Governor General of Eastern Roumeli by the Nafplion Government. Though he was successful initially in halting the advance of Aslan Bey’s men near Bralos, his resources began to run dry. Gouras faced a similar problem as the Ottoman garrison in Khalkis regularly sortied across the Euripus Strait to raid his rear, diverting his own limited resources as well, enabling his opponent Osman Aga to make some gains along the coast. Reinforcements were also in short supply given the invasion of Ibrahim Pasha in the Morea and the beginning of the Third Siege of Missolonghi. Despite their valor, Androutsos and Gouras simply lacked the men and munitions to hold off the Turks indefinitely, still they made them pay for every plot of land they took. Ultimately, through sheer numbers the Ottomans forced the Greeks to cede ground and by the beginning of August, they had taken the hamlets of Bralos and Agios Konstantinos.

Yannis Gouras Ambushes the Turks near Livanates

The arrival of Charles Fabvier in Salona in August did much to sure up the flagging Greek defenses in the region. His experience as an engineer proved dividends in the hills and valleys of Phocis and Phthiotis, slowing the Turkish advance into a crawl in some places or halting it entirely in others. By the end of November 1825, the theater had stalemated as the Ottomans withdrew into Winter Quarters, effectively ending the offensive halfway. The coming of Spring in 1826 saw a resumption of the Ottoman attack, and like before, they slowly, yet methodically pushed the Greeks southward. Androutsos, however, opted to make his stand at Gravia, where he had famously defeated the Albanian Omer Vrioni nearly five years earlier.

Despite being outnumbered nearly 10 to 1, Androutsos and 622 men successfully held off Aslan Bey and 5,800 Ottoman soldiers. Unable to crack the Greeks’ defenses after five long days, Aslan Bey was forced to call for reinforcements from Lamia. Fabvier, however, had managed to elude detection and positioned himself and nearly 240 Greeks and Philhellenes in the hills between Gravia and Lamia. When 1,100 Ottoman soldiers appeared along the road near Skamnos, Fabvier sprung his trap. 90 Ottomans were killed in the initial volley and another 370 would be lost in the subsequent hours, but by nightfall they had managed to link up with Aslan Bey when he dispatched his cavalry to rescue them. Despite getting his reinforcements, the existent of a small, but relatively sizeable force of Greeks to his rear made Aslan Bey’s situation increasingly untenable. The number of hostile Greeks in the area continued to rise every day as more and more men came to share in the glory of the looming victory. Seeking to avoid a repeat of Dramali’s Disaster, Aslan Bey decided to withdraw to Lamia, hounded all the way by opportunistic Greeks. While he managed to reorganize his forces, and was reinforced with additional men from Missolonghi, Aslan Bey proved reluctant to march forth once again, and instead opted to remain cloistered away in Lamia for several months.

With the situation in Phocis stabilized for now, Fabvier was tasked with leading his men West to Nafpaktos to aid in the defense of the city. The situation in the region had barely changed in the two months since the siege began on the 24th of July. While Yusuf Pasha had finally managed to complete his trenches around the city in early August, they were just as porous as the naval blockade outside the city’s harbor, and the arrival of 11 more ships and 2,500 more soldiers in late August did little to rectify the mounting problems for the Ottomans. The Greek garrison within Nafpaktos had similarly grown from 900 to 1,600 by the time Fabvier arrived in early September. What’s more, Markos Botsaris, Demetrios Makris, and many of the surviving soldiers from Missolonghi constantly raided the Ottoman camp, disrupting their supply lines, cutting off their lines of communication, attacking their sentries, and effectively making life miserable for Yusuf Pasha and his men.

When Fabvier arrived on the scene on the 26th of September with 2,900 regulars and irregulars to break the siege of Nafpaktos, Yusuf Pasha immediately turned his attention to this new threat, bringing 5,000 Ottoman soldiers and the entirety of his cavalry to greet them. Fabvier in preparation for their attack, readied rudimentary defenses and loaded grapeshot and shrapnel into his field guns, which he unleashed as soon as the Ottomans began to ford the Mornos river. Fabvier’s regulars, his Taktikon Infantry, stood shoulder to shoulder in line formation leveled their guns on the charging Ottomans and fired in a disciplined display of withering firepower.[3] Though the opening volley was certainly devastating, Yusuf and his men managed to overcome the paltry defenses and engage the Greeks in hand to hand combat. It was an intense affair, but Fabvier and his men conducted themselves admirably given the circumstances and held their ground until nightfall, effectively ending the battle. When morning came on the 27th of September, Yusuf Pasha discovered the Greeks had fled the field during the night.

In truth, Fabvier and his regulars had withdrawn in good order to the coast where they embarked on a fleet of transports to carry them into the city under the cover of darkness. The klephts and militia that had joined with him would continue to harass the Ottomans from the hills and forests to the East in conjunction with Botsaris and Makris to the North and West respectively. After nearly three months the Ottomans had made little progress against Nafpaktos and what they had gained they had achieved at a steep price. The final death knell for the Ottoman siege of Nafpaktos would come not on land, but at sea.

On the 10th of October, the Greek Admiral Andreas Miaoulis and 12 Greek ships, the 4th Rate Hellas, the 4th Rate Kronos, the frigate Leandros, the corvette Hydrai, the corvette Spetsei, and the steamship Karteria, among several others forced their way through the straits of Rio, brushing aside the cannon fire from the castles of Rio and Antirrio before beginning their attack on the Ottoman blockade of Nafpaktos. Though outnumbered 30 to 14, the Greeks, for the first time in the war possessed larger and more powerful ships than the Ottomans. The Karteria under the precise command of Captain Hastings proved especially deadly in this engagement, sinking 5 Ottoman ships by itself. Though coal was a precious resource in Greece, Hastings had rationed his stockpile expertly, saving it solely for situations such as these. With his furnaces running, Hasting’s ordered his crew to heat their shots and fire their carronades with less gunpowder so to imbed the shot within the planks of the enemy’s hull. The tactic worked brilliantly, setting three ships aflame and sinking two others in quick order. It was truly a marvel to behold for the Greeks, witnessing the steamship operate as it did. Traveling at about 8 knots, it smoothly maneuvered through the fighting ships confusing the Ottomans and amazing the Greeks.

The Karteria in Battle at Nafpaktos

Miaoulis also shared in the glory, sinking 3 Ottoman vessels with the Hellas. Of all the naval engagements of the war, the battle of Nafpaktos was among the most one sided. Within all of two hours, the Ottoman “fleet” was sent running or sent to the bottom of the sea, the Greeks only suffering some slight to moderate damage on four of their ships and the loss of about 28 sailors and marines. The Greeks, now possessing naval supremacy began to shell the Ottoman positions on land and escorting transports into the city from the Morea. Unable to maintain his lines, Yusuf Pasha was forced to abandon the siege of Nafpaktos and retreat to Missolonghi. The Greeks would deliver one last blow to the Ottoman commander.

To the north of Krioneri, all of 10 miles from Missolonghi, the Ottoman army was ambushed by 1,300 Greeks and Souliotes under the command of Botsaris and Makris. Exhausted, starving, and ill equipped for a sudden confrontation, the Greeks fell upon the beleaguered Ottomans. In an instant, their morale vanished, their discipline failed them, and they chose to run and flee rather than stand and fight. In the chaos that ensued, over half of the 4,600 Ottomans that remained were captured or killed. Some, including Yusuf Pasha ran to the safety of Antirrio, while others managed to reach the sanctity of Missolonghi’s walls, the irony of which was not lost on the Greeks. For so long, those walls had protected the Greeks from the Ottomans, now they protected the Ottomans against the Greeks. Whatever the case may be, the Ottoman position in Western Greece had completely collapsed and it was only a matter of time before Missolonghi was once more in Greek hands.

Greece in the Fall of 1826

Purple – Greece

Green – Ottoman Empire

Pink – The United States of the Ionian Islands

Next Time: Scourge No More

[1] Many die hard Bonapartists fled France and Italy for Britain or Spain in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. Eventually, many returned to France to take part in the 1830 July Revolution, Fabvier himself took part in the event as well, serving as the Commander of revolutionaries in Paris.

[2] As was the case across Greece, many men who fought for the Greeks went without pay, Androutsos was no exception. Having gone months without pay, and losing men and resources to other captains in favor with the Government, Androutsos, opened negotiations with the Ottomans regarding his defection. Unfortunately for Androutsos, he was captured by the Greeks in an ensuing battle, some accounts say he surrendered willingly, and was summarily imprisoned at the Acropolis where he was later found dead on the 17th of June 1825.

[3] Taktikon is the Greek name for the modern European style army that they developed in the later years of the war.

The Greeks Assemble outside Nafpaktos

The fall of Missolonghi was met with muted celebration across the Ottoman Empire, with the loudest cheers of jubilation coming from Topkapi Palace in Constantinople. The infernal city had finally fallen to the Sultan’s armies, and there was no one more thrilled at the result than Sultan Mahmud II himself. By his command, the minarets throughout the city proclaimed the glories of Allah and the victories of his servants over the traitorous Greeks. Surprisingly, the least enthused about Missolonghi’s capture were the Ottoman soldiers themselves. Rumors spread across the empire, that it was the Egyptians and not the Turks who were responsible for the victory over the Greeks and rather than boosting their morale, it only fell further as a result.

The yearlong undertaking needed to take the city had been great, of the 50,000 Albanian, Egyptian, and Turkish soldiers sent against the Greeks in the lagoon and in the city, over 18,000 had died, with as many men succumbing to illness as those who succumbed to Greek bullets or blades. Another 15,000 had been so badly mauled in the fighting or made to suffer from other maladies that they were rendered unfit for further combat against the Greeks, with most being mustered out of service entirely or relegated to garrison duty. Over the next month following the capitulation of Missolonghi, their numbers were reduced further still. His obligation fulfilled, Ibrahim and his remaining 4,500 men, many of which were wounded, departed for the Morea to complete his conquests there. Another 2,000 were called away to the East to aid in the last push against the Greeks of Atalanti and Salona. The Greeks who had escaped from Missolonghi also continued to prey upon the Ottomans when they ventured too far from their camps, killing or wounding an additional 2,300 Albanians and Turks between the beginning of May and the end of July.

Command of the army was also an issue for the Ottomans. The death of Resid Mehmet Pasha in January had left the Ottoman troops effectively under the command of Ibrahim Pasha, but his departure soon after the siege’s conclusion in early May had now left them without a clear leader once again. The only other Ottoman commanders of any significance present at Missolonghi were the Kapudan Pasha, Khosref Pasha and Yusuf Sezeris, the Pasha of Euboea. Both men, however, refused to concede leadership to the other and as a result they did little more than argue for the next two months before Khosref Pasha was finally recalled to Constantinople in early July. Now alone, Yusuf Pasha set about installing garrisons in Missolonghi and its environs before he acted on orders of his own, the reconquest of Nafpaktos. The city and castle had fallen to the Greeks right from underneath Yusuf over two years ago, now was the chance for him to regain his lost honor.

Reaching Nafpaktos on the 24th of July, with 6,000 infantrymen and 500 cavalrymen, he found the city and its castle lightly defended by no more than 900 Greeks in total, many of whom were likely townsfolk who had been levied for the defense of their city. His good fortune quickly ran out, however. While he could establish siege works along the western edge of the city, his efforts to the North and East were met with great resistance from the Greeks of Nafpaktos. Reinforcement by sea also proved to be an aggravating problem for the Ottomans as the Egyptian fleet had departed with Ibrahim, and much of the Ottoman Navy had left with Khosref Pasha leaving Yusuf with little more than 3 sloops, 2 brigs, and several smaller vessels to maintain a porous blockade around Nafpaktos. While the Ottomans held the Gulf of Patras, the Gulf of Corinth lay entirely in Greek hands, enabling them to quickly rush men and supplies into the city at a moment’s notice. One of those men was the French Philhellene Charles Fabvier.

Colonel Charles Nicolas Fabvier, French Officer and Philhellene

Colonel Charles Nicholas Fabvier had served as an artillery officer and engineer in the armies of France during the Napoleonic wars. Fabvier had an illustrious military career under Napoleon serving with distinction in the Ulm Campaign, Russian Campaign, the Hundred Days Campaign and as a part of various diplomatic missions to the Ottoman Empire and Persia. His career was derailed by injuries which limited his time in the field of battle where he could gain glory or élan. Fabvier continued his service to France after the restoration of the Bourbon Monarchy in 1815 but due to his strong association with the Revolution he was relegated to a minor role. After being charged with a crime he did not commit and repeatedly subjected to ridicule over his liberal beliefs, he was finally pushed out of the French Army entirely in 1823. With nowhere else to turn, he and a group of other French and Italian Bonapartists embarked on a ship bound for Greece to make a new beginning for themselves in Hellas.

Arriving at Navarino in the Summer of 1824, Charles Fabvier intended to establish an agricultural and industrial colony with his fellow expatriates in Greece, but the needs of the Revolutionary Government compelled him to act in its defense.[1] Barely a month after arriving in Greece, Fabvier left for Britain to lobby additional support for the Greeks in London, where he raised funds and gathered volunteers to serve in Greece. After spending a year in Britain, he returned to Nafplion in mid-June of 1825, just in time for Ibrahim Pasha’s attack on the city. Fighting alongside Yannis Makriyannis in the battle of Lerna, Fabvier fought heroically alongside the Greeks earning their trust and comradery. For his valor, the Government, appointed him command of the 2nd Regiment of the Hellenic Army which was presently in Southern Roumeli outside Salona. The move also put him under the command of Odysseus Androutsos, the recently appointed Governor General of Eastern Roumeli.

Androutsos had made amends with the Government in Nafplion over the Summer and Fall of 1824, due in large part to Byron’s payment of his arrears. Trewlany and Stanhope had both insisted upon Byron to finance their benefactor Androutsos, and while he was nowhere near as devoted to the man as his companions were, Byron recognized the importance of retaining the services of this talented man for the Greeks. Using his position as the custodian of the first English loan, Byron had the Nafplion Government pay Androutsos and their men for their services and bestowed upon them new weapons and fresh munitions. The apparent show of support galvanized Androutsos, as his vigor had been waning in the months following the disappointment that was the Congress of Salona, and compelled him to act. The news of his hated rival Ioannis Kolettis’ withdrawal from the Executive following his grievous injury at the hands of Charalamvis in January also pleased the klepht and did much to reconcile him with the Nafplion Government. [2]

Together with his deputy Yannis Gouras, Androutsos moved North from Athens to fight off the Ottoman offensives towards Atalanti, Livadeia, and Salona for which he was named Governor General of Eastern Roumeli by the Nafplion Government. Though he was successful initially in halting the advance of Aslan Bey’s men near Bralos, his resources began to run dry. Gouras faced a similar problem as the Ottoman garrison in Khalkis regularly sortied across the Euripus Strait to raid his rear, diverting his own limited resources as well, enabling his opponent Osman Aga to make some gains along the coast. Reinforcements were also in short supply given the invasion of Ibrahim Pasha in the Morea and the beginning of the Third Siege of Missolonghi. Despite their valor, Androutsos and Gouras simply lacked the men and munitions to hold off the Turks indefinitely, still they made them pay for every plot of land they took. Ultimately, through sheer numbers the Ottomans forced the Greeks to cede ground and by the beginning of August, they had taken the hamlets of Bralos and Agios Konstantinos.

Yannis Gouras Ambushes the Turks near Livanates

The arrival of Charles Fabvier in Salona in August did much to sure up the flagging Greek defenses in the region. His experience as an engineer proved dividends in the hills and valleys of Phocis and Phthiotis, slowing the Turkish advance into a crawl in some places or halting it entirely in others. By the end of November 1825, the theater had stalemated as the Ottomans withdrew into Winter Quarters, effectively ending the offensive halfway. The coming of Spring in 1826 saw a resumption of the Ottoman attack, and like before, they slowly, yet methodically pushed the Greeks southward. Androutsos, however, opted to make his stand at Gravia, where he had famously defeated the Albanian Omer Vrioni nearly five years earlier.

Despite being outnumbered nearly 10 to 1, Androutsos and 622 men successfully held off Aslan Bey and 5,800 Ottoman soldiers. Unable to crack the Greeks’ defenses after five long days, Aslan Bey was forced to call for reinforcements from Lamia. Fabvier, however, had managed to elude detection and positioned himself and nearly 240 Greeks and Philhellenes in the hills between Gravia and Lamia. When 1,100 Ottoman soldiers appeared along the road near Skamnos, Fabvier sprung his trap. 90 Ottomans were killed in the initial volley and another 370 would be lost in the subsequent hours, but by nightfall they had managed to link up with Aslan Bey when he dispatched his cavalry to rescue them. Despite getting his reinforcements, the existent of a small, but relatively sizeable force of Greeks to his rear made Aslan Bey’s situation increasingly untenable. The number of hostile Greeks in the area continued to rise every day as more and more men came to share in the glory of the looming victory. Seeking to avoid a repeat of Dramali’s Disaster, Aslan Bey decided to withdraw to Lamia, hounded all the way by opportunistic Greeks. While he managed to reorganize his forces, and was reinforced with additional men from Missolonghi, Aslan Bey proved reluctant to march forth once again, and instead opted to remain cloistered away in Lamia for several months.

With the situation in Phocis stabilized for now, Fabvier was tasked with leading his men West to Nafpaktos to aid in the defense of the city. The situation in the region had barely changed in the two months since the siege began on the 24th of July. While Yusuf Pasha had finally managed to complete his trenches around the city in early August, they were just as porous as the naval blockade outside the city’s harbor, and the arrival of 11 more ships and 2,500 more soldiers in late August did little to rectify the mounting problems for the Ottomans. The Greek garrison within Nafpaktos had similarly grown from 900 to 1,600 by the time Fabvier arrived in early September. What’s more, Markos Botsaris, Demetrios Makris, and many of the surviving soldiers from Missolonghi constantly raided the Ottoman camp, disrupting their supply lines, cutting off their lines of communication, attacking their sentries, and effectively making life miserable for Yusuf Pasha and his men.

When Fabvier arrived on the scene on the 26th of September with 2,900 regulars and irregulars to break the siege of Nafpaktos, Yusuf Pasha immediately turned his attention to this new threat, bringing 5,000 Ottoman soldiers and the entirety of his cavalry to greet them. Fabvier in preparation for their attack, readied rudimentary defenses and loaded grapeshot and shrapnel into his field guns, which he unleashed as soon as the Ottomans began to ford the Mornos river. Fabvier’s regulars, his Taktikon Infantry, stood shoulder to shoulder in line formation leveled their guns on the charging Ottomans and fired in a disciplined display of withering firepower.[3] Though the opening volley was certainly devastating, Yusuf and his men managed to overcome the paltry defenses and engage the Greeks in hand to hand combat. It was an intense affair, but Fabvier and his men conducted themselves admirably given the circumstances and held their ground until nightfall, effectively ending the battle. When morning came on the 27th of September, Yusuf Pasha discovered the Greeks had fled the field during the night.

In truth, Fabvier and his regulars had withdrawn in good order to the coast where they embarked on a fleet of transports to carry them into the city under the cover of darkness. The klephts and militia that had joined with him would continue to harass the Ottomans from the hills and forests to the East in conjunction with Botsaris and Makris to the North and West respectively. After nearly three months the Ottomans had made little progress against Nafpaktos and what they had gained they had achieved at a steep price. The final death knell for the Ottoman siege of Nafpaktos would come not on land, but at sea.

On the 10th of October, the Greek Admiral Andreas Miaoulis and 12 Greek ships, the 4th Rate Hellas, the 4th Rate Kronos, the frigate Leandros, the corvette Hydrai, the corvette Spetsei, and the steamship Karteria, among several others forced their way through the straits of Rio, brushing aside the cannon fire from the castles of Rio and Antirrio before beginning their attack on the Ottoman blockade of Nafpaktos. Though outnumbered 30 to 14, the Greeks, for the first time in the war possessed larger and more powerful ships than the Ottomans. The Karteria under the precise command of Captain Hastings proved especially deadly in this engagement, sinking 5 Ottoman ships by itself. Though coal was a precious resource in Greece, Hastings had rationed his stockpile expertly, saving it solely for situations such as these. With his furnaces running, Hasting’s ordered his crew to heat their shots and fire their carronades with less gunpowder so to imbed the shot within the planks of the enemy’s hull. The tactic worked brilliantly, setting three ships aflame and sinking two others in quick order. It was truly a marvel to behold for the Greeks, witnessing the steamship operate as it did. Traveling at about 8 knots, it smoothly maneuvered through the fighting ships confusing the Ottomans and amazing the Greeks.

The Karteria in Battle at Nafpaktos

Miaoulis also shared in the glory, sinking 3 Ottoman vessels with the Hellas. Of all the naval engagements of the war, the battle of Nafpaktos was among the most one sided. Within all of two hours, the Ottoman “fleet” was sent running or sent to the bottom of the sea, the Greeks only suffering some slight to moderate damage on four of their ships and the loss of about 28 sailors and marines. The Greeks, now possessing naval supremacy began to shell the Ottoman positions on land and escorting transports into the city from the Morea. Unable to maintain his lines, Yusuf Pasha was forced to abandon the siege of Nafpaktos and retreat to Missolonghi. The Greeks would deliver one last blow to the Ottoman commander.

To the north of Krioneri, all of 10 miles from Missolonghi, the Ottoman army was ambushed by 1,300 Greeks and Souliotes under the command of Botsaris and Makris. Exhausted, starving, and ill equipped for a sudden confrontation, the Greeks fell upon the beleaguered Ottomans. In an instant, their morale vanished, their discipline failed them, and they chose to run and flee rather than stand and fight. In the chaos that ensued, over half of the 4,600 Ottomans that remained were captured or killed. Some, including Yusuf Pasha ran to the safety of Antirrio, while others managed to reach the sanctity of Missolonghi’s walls, the irony of which was not lost on the Greeks. For so long, those walls had protected the Greeks from the Ottomans, now they protected the Ottomans against the Greeks. Whatever the case may be, the Ottoman position in Western Greece had completely collapsed and it was only a matter of time before Missolonghi was once more in Greek hands.

Greece in the Fall of 1826

Purple – Greece

Green – Ottoman Empire

Pink – The United States of the Ionian Islands

Next Time: Scourge No More

[1] Many die hard Bonapartists fled France and Italy for Britain or Spain in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. Eventually, many returned to France to take part in the 1830 July Revolution, Fabvier himself took part in the event as well, serving as the Commander of revolutionaries in Paris.

[2] As was the case across Greece, many men who fought for the Greeks went without pay, Androutsos was no exception. Having gone months without pay, and losing men and resources to other captains in favor with the Government, Androutsos, opened negotiations with the Ottomans regarding his defection. Unfortunately for Androutsos, he was captured by the Greeks in an ensuing battle, some accounts say he surrendered willingly, and was summarily imprisoned at the Acropolis where he was later found dead on the 17th of June 1825.

[3] Taktikon is the Greek name for the modern European style army that they developed in the later years of the war.

Last edited: