Chapter 55: Ethos and Mythos

The Lion Gate of Mycenae

An important, yet often understated decision by Greek Prime Minister Andreas Metaxas and his Government was the renaming of the Phoenix in the Fall of 1841. Over the course of its 14-year existence, the Phoenix developed a rather poor reputation among the Greek people as a relatively unlikeable and worthless currency. The reason for this poor reception dates back to the origin of the Phoenix during the waning months of the War for Independence, when then Governor of Greece Ioannis Kapodistrias unilaterally pronounced the Phoenix as the official currency of an independent Greece. Despite purchasing a coin press in Malta, ordering special coin dies from the Armenian jeweler Chatzigrigoris Pyrobolistis, and establishing a minting facility at Aegina, Greece simply lacked the necessary raw resources - gold, silver, and copper - to make the coins in a sufficient quantity.

All told, between January 1827 and May 1830, only 20,000 silver Phoenix coins and a handful of gold Phoenix coins would be produced. The resulting shortfall in available capital in Greece during the formative years of the currency almost certainly doomed the Phoenix to failure as its reputation among the people suffered and the Government’s attempts to rectify this issue only exacerbated it even more when they began printing paper Phoenix banknotes. Lacking the same integral weight and value as the silver and gold coins, the people spurned them in favor of foreign currencies like the Ottoman Piastre, the French Franc, or the British Pound. Even when the Greek Government committed itself to continue supporting the Phoenix after the war and purchased the resources needed to produce them, it was too late as the Phoenix had been thoroughly discredited among much of the Greek people and many members of the Government.

The Phoenix would only survive until the dawn of the 1840’s thanks to the efforts of Prime Minister Ioannis Kapodistrias who stubbornly refused to concede the issue to his economic advisors. Kapodistrias would even go as far as to sack his own Treasury Minister Georgios Kountouriotis in 1833 for refusing to enforce a law prohibiting Ottoman Piastres from being used in Government venues. However, with Kapodistrias’ retirement from public office in February 1841, the Phoenix had lost it most prominent and vocal supporter as his successor Andreas Metaxas would prove himself to be much less emotionally and politically attached to the Phoenix. Metaxas generally agreed with the Phoenix’s detractors and ultimately announced his intention to rename the currency several weeks after assuming the office of Prime Minister in the Summer of 1841.

The process of rebranding the Phoenix was done in a respectful and proper manner, as numerous names, designs, and breakdowns of the new currency were considered ad nauseam. Eventually though, Metaxas and his compatriots decided upon the Drachma in early October. The Drachma (₯) would replace the Phoenix at par and it would be comprised of the same precious metals (90% silver and 10% copper) for a 1 Drachma coin while the 20 Drachma coin would be comprised primarily of gold just like the 20 Phoenix coins had been. The Lepta would also remain unchanged as the primary subdivision of the Drachma, with 1 Lepta being worth 1/100th of a Drachma. The design of the Drachma would feature King Leopold’s profile on the face of the coin, and the coat of Arms of Greece on the reverse replacing the unpopular phoenix emblem. Phoenixes would be allowed to continue circulation throughout the Greek economy indefinitely, however, the production of new Phoenixes would be halted effective immediately upon the start of the production of the Drachma in late November. Additionally, any Phoenixes collected by the Greek Government through taxes, fines, donations, or any other means going forward would be destroyed and/or converted into new Drachma.

Drachma Coins and Banknotes

The reasoning for the choice of Drachma is rather obvious given the cultural and historical importance associated with the name. As the most prominent and widespread currency in the Ancient Greek world, the Drachma possessed a degree of prestige and legitimacy among the Greeks that the Phoenix simply never could attain. The reception of the Drachma also benefitted immensely from the opening of the silver mines at Laurium nearly two years earlier, which helped to reduce the chronic silver shortages that had unfortunately plagued the Phoenix throughout its short existence. As a result, the Drachma enjoyed a great deal of popular support among the people of Greece and from their friends abroad who praised the Greek Government for their fresh start.

The resurrection of the Drachma also coincided with an important development in the field of archaeology in the Kingdom of Greece. In what was to be the first of many, the French Government announced their decision to begin construction on a school of archaeology in Athens. The French School of Athens, as it was officially known would aid French and Greek archaeologists in the surveying, recording, and excavating of the various ruins, abandoned settlements, and ancient wonder scattered across the Greek countryside. The School would also train prospective students in the modern art of archaeology through lectures and field trips to various sites around Greece. The French School would also work alongside the National Archaeological Museum of Athens and the Archaeological Society of Athens in many of their own expeditions as well.

The main sites targeted by these groups were the Acropolis in Athens which saw the most activity over the years, the ancient sanctuary of the Hellenic Gods at Olympia, the Temple of Poseidon at Sounion, the island of Delos, and the sanctuary of Apollo and the Delphic Oracle at Delphi among many others. Some Medieval structures like the Frankish palace at Mystras, the Hexamilion Wall near Corinth, and the Byzantine Church of Panagia Kapnikarea in Athens, the Nea Moni monastery of Chios, and the Church of Paregoretissa in Arta attracted some interest as well, albeit on a much lower scale compared to their classical counterparts. Surprisingly, however, a Bronze Age site predating even the golden age of Greek democracy, culture, and architecture would soon attract a substantial degree of attention over the course of 1841, 1842, and 1843. On the 28th of August 1841, a team of 7 laborers under the direction of the Greek archaeologist Kyriakos Psistakis began working in and around the ancient city of Mycenae, with their primary task being the restoration of the famous Lion Gate.

[1]

Mycenae was a city steeped in myth and legend, famous for its status as the capital of the mighty King Agamemnon from Homer’s Epics, the

Iliad and the

Odyssey and for its brief, but very detailed depiction in the tragedy

Oresteia by Aeschylus. While the local Greeks had known of the abandoned settlement for countless generations, little archaeological and historical evidence actually existed linking the ruined Argolic city with Homer’s “Golden Mycenae”. The Greek geographer Pausanais had written of the city during his many travels in the Second Century, and the Venetian Provveditore Generale Francesco Grimani had briefly mentioned a site resembling Mycenae in his survey of the Morean countryside in 1700. Sadly, however, the site was relatively untouched throughout the intervening years and would only experience any large degree of activity in the Fall of 1841 when Psistakis and his team began work at the site.

Map of the Mycenae Acropolis

Over the years falling rocks, loose soil, random debris, and untamed vegetation had built up around the ancient settlement making the site almost unnoticeable from the road below. Now Psistakis and his men began the grueling task of clearing the outer walls and the distinctive Lion Gate, a project that would take nearly a month to complete. Progress was dreadfully slow as funding remained a constant issue for the team of archaeologists and laborers as resources were diverted to more lucrative expeditions. Yet their efforts quickly began to attract attention from both the archaeological community in Greece and the Greek Government. Eventually, Psistakis and his team would finish their work on the Lion Gate as well as much of the Cyclopean and Ashlar walls on the 2nd of October 1841 to the cheering of a small crowd that had gathered nearby.

[2] Aside from twenty or so local villagers and goat herders who had stopped by to witness the spectacle, there were a half dozen journalists to record the event, a pair of representatives from the National Archaeological Museum, one observer from the French School, five men from the Archaeological Society of Athens who had sponsored the expedition, and most surprisingly, King Leopold himself.

At first glance, King Leopold was not a man many would have expected to see at a dusty and dirty archaeological site far from the luxury and comfort of the capital. Yet, while his public façade had grown cold over the years by cynicism, heartbreak, and personal tragedy; he remained a romantic at heart who desperately yearned to fulfill his romantic urges through adventure and artistic endeavors. “I think it will be very pleasant to breathe the balmy Aegean air, to wander through groves of myrtle, olives, and oranges, and to sit beneath blue silk tents while beautiful Greek women dance their tremendous dances before me. To visit the ancient ruins, to travel across a land of great wonders and greater men shall satisfy the poetic needs of my soul.” -Leopold of Saxe Coburg and Gotha to Christian Friedrich Freiherr von Stockmar in March 1830

It was no secret that Leopold had accepted the Greek crown primarily for the past prestige and sophistication that the land had once held, rather than the present rural and uncouth country that it had become. Yet even still, the ruins and abandoned settlements that dotted the Greek countryside inspired Leopold to restore the past grandeur and greatness of Greece. To that end he became a prominent supporter of the arts and archaeology in Greece. He patronized various artists across the country like the painters Dionysios Tsokos who painted Leopold’s state portrait in 1843 and Andreas Kriezis who decorated the Royal Palace in Athens. He hired sculptors for various projects and he sponsored writers for many translations and duplications of ancient texts. Leopold also made a point of visiting various archaeological sites which he deemed to be historically and culturally important to Greek history and culture like Mycenae.

The State Portrait of King Leopold by Dionysios Tsokos

With the Lion Gate cleared, Leopold thought it best to travel to the site in person to see it for himself. Impressed by Psisakis’ work, King Leopold encouraged the archaeologist and his team to expand their excavation of Mycenae from the gateway and outer walls to the Citadel and upper city itself. This would be a herculean task which would undoubtably require multiple years of hard work to fully clear and thousands upon thousands of Drachmae to pay for the crew of laborers and archaeologists that would be needed throughout the expedition. Yet the King, his ministers, the National Archaeological Museum, and the Archaeological Society of Athens all backed the endeavor and a tentative starting date for the second round of excavations at Mycenae was scheduled for the following Spring.

When Psisakis and his men returned to Mycenae in early March 1842, they did so with an army of laborers, historians, and archaeologists at their back. They were also joined periodically by several foreign archaeologists who came to aid in the excavation from time to time, the most prominent being the Frenchmen Jean Antoinne Letronne and Charles Lenormant, the Prussian Karl Otfried Muller, and the Lübecker Ernst Curtius among a few others. Initially, work was to be focused in and around the acropolis of Mycenae in an area believed to be the site of the ancient palace. Yet several days into the expedition, their plans would change completely as a series of mounds near the entrance to the town attracted their attention.

From a distance they appeared to be a natural feature of the site, but upon a closer inspection one could see that they were in fact burial mounds. Immediately, their focus shifted to the graves which quickly revealed a series of ancient stone stelae. The burial markers bore images resembling chariot races, battle scenes, or hunts among other impressive feats of strength or power. Inspired by the belief that they had stumbled upon the burial sites of the ancient Mycenaean Kings of yore, the team quickly began work removing the dirt from atop the graves. Digging deeper, they would quickly discover a set of six shaft graves underneath the mounds which contained 19 bodies in total, 8 men, 9 women, and 2 children. Accompanying the bodies were a number of jewels and precious stones as well as an untold number of gold, silver, and bronze artifacts ranging from rings and bracelets to swords and scepters. The most awe-inspiring piece, however, was a golden burial mask depicting a older man’s face. As it was the most impressive and prominent find in the graves, many of the archaeologists began calling it Agamemnon’s Death Mask, in honor of the great Mycenaean King of legend.

The discovery of Agamemnon’s Death Mask was quickly followed up by the recovery of a golden goblet believed to be King Nestor’s famous Cup from the

Iliad. The recovery of two items associated with two key figures from the Epics of Homer brought several men to tears, and then quickly thereafter raucous celebration filled with drinking, dancing, feasting, music, and merriment. Yet when the party came to an end and the sun rose the following morning, the team of archaeologists, historians, and laborers assembled at Mycenae discovered to their horror that Agamemnon’s Death Mask, the Cup of Nestor and an untold number of gold and silver rings, bracelets, necklaces, headpieces, and chalices had been stolen. A quick rollcall would reveal that six men had deserted from the camp during the night making them the most obvious suspects to have absconded with the missing treasures.

Immediately, a team of riders were dispatched to notify the local authorities at Nafplion as to theft at Mycenae. Fortunately, by the end of the day four of the six missing men had been captured, and their ill-gotten goods were recovered, including Agamemnon’s Death Mask and King Nestor’s Cup. Sadly, two men would manage to escape the authorities and flee overseas to Italy and from there to France and Germany where they subsequently sold the stolen artifacts to the highest bidders. Although many of the treasures would eventually be restored to Greece in the coming months and years, the entire incident was a terrible embarrassment to the Greek Government that had caused them needless headache and humiliation. It also served as a harsh reminder of the loss of the Elgin Marbles nearly three decades earlier.

The Elgin Marbles, as they were known to the British public, were a massive collection of statues, sculptures, and friezes recovered from the Acropolis in Athens by the former British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Lord Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin. While most of the marbles were taken from the Parthenon, several works came from the Erechtheion, the Propylaea, and the Temple of Athena Nike; all of which represent approximately half of the surviving pieces from the Acropolis today. The process of excavating and removing the sculptures to Britain took many years to accomplish, beginning in 1803 and finishing in 1812, and required the complicity of the local Ottoman authorities. As the Acropolis was still a military fortification of the Ottoman Army at that time, chicanery was needed to gain access to the site. To that end, Elgin presented a dubious translation of what he proclaimed to be a Firman from the Sultan Selim III allowing him and his associates permission to the Acropolis. A second Firman of similar questionability also permitted Elgin and his men permission to remove the sculptures from the site and send them to Britain. While the means of taking the marbles were bad enough, the justification for his actions were equally disturbing.

Although Eglin presented his actions in the light of an altruist philanthropist seeking to preserve these artistic wonders for posterity, in truth, his pilfering of the Acropolis Marbles was done out of a vain desire to decorate his manor in Scotland. Even then, the Marbles would not remain at his home of Broomhall for long, as a costly legal battle with his wife the Lady Mary Nisbet would force Elgin to sell the Marbles to the British Government to pay his arrears in 1816. The Elgin Marbles were then bestowed upon the British Museum and remained with them ever since, throughout the years of the Greek War of Independence and into the first years of the nascent Kingdom of Greece.

The removal of the Elgin Marbles from the Acropolis proved to be a touchy subject the Greeks themselves. Though they had not been consulted on the matter during the original removal of the Acropolis Marbles and the Greek state had not been independent at the time of the act, the Greek government continually requested that the Marbles be returned to them as the rightful heirs of Ancient Greece. These requests were continually rejected by the British Government as the pieces had become quite popular among the British public by the 1830’s and the matter was ultimately deadlocked for many years to come. Even the aid of the great writer and Philhellene, Lord Byron proved insufficient to the task of convincing the British Museum to return the Marbles.

[3] The matter would only come to the foreground of British-Greek relations in 1841 thanks to the death of the Earl of Elgin in mid-November of that year.

As had been the case with the prior meetings on the Elgin Marbles, however, the December 1841 negotiations ended in failure. Despite offers by the Greek Government to make perfect replicas of the Elgin Marbles from Pentelic marble, the British refused to return them. Even a desperate bid to buy the marbles was turned down much to the despair of the Greek representatives. Sadly, the unresolved matter would serve as a minor blemish on the otherwise excellent relationship between Great Britain and Greece. However, the failure of the 1841 Elgin Marble Negotiations would help bring about some reforms of archaeological practices in Greece, especially after the incident at Mycenae and the theft of various artifacts from the dig site there the following Spring.

Going forward, the Greek Government expressed its desire to exhibit more control over the countless ancient ruins, structures, treasures, and artifacts throughout Greece. It required that a member of the Internal Affairs Ministry be present at all active excavation sites across the country and that all artifacts be brought to the attention of the Greek Government. While the thefts of ancient artifacts by day laborers, archaeologists, and random passersby would continue, they did decline by a moderate margin. Despite the success of these new policies, they were not a perfect solution as many harmful excavation practices had remained unresolved and would sadly continue for years to come.

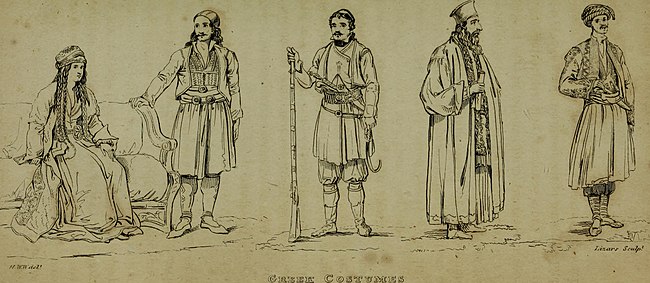

While some elements of Greek culture looked to the past other aspects looked to the West especially in regards to dress and literature. During the Ottoman era in Greece, clothing had been extensively regulated by the Sublime Porte which forced people to dress according to their religion and profession. Most men from the rural Greek countryside tended to wear the fustanella with a tunic, fez, leggings, and pair of simple leather shoes or boots, although the exact colors and materials used varied from region to region. The islanders and sailors of Ottoman Greece generally wore a similar costume with a pair of knee breeches called “vraka” instead of the mainlander’s fustanella. Men of wealth and prominence, such as the Phanariotes or successful merchants generally favored the attire of western courts such as breeches, coats, and ties as they tended to interact with merchants and diplomats from the West.

The Greek War of Independence and the liberation of Greece in 1830 would see little in the way of immediate change regarding Greek fashion despite doing away with the Ottoman laws which had determined dress in Ottoman Greece. But, by the late 1830’s and especially by the start of the 1840’s Western apparel began making greater inroads among Greek men in the middle and lower classes of Greek society, particularly those living in the major city centers of Greece. Despite these changes in Greek dress during this period, the traditional fustanellas, vrakas, and tunics of earlier years remained incredibly popular among the Greeks. The fustanella did experience some changes during this time as it generally became shorter in length, rising from just below the knee to just above it in the years following the War for Independence.

Women’s dresses would also experience a noticeable change as well thanks in large part to the influence of the young Queen Marie. Seeking to ingratiate herself in her new land, Queen Marie developed her own version of the traditional Greek woman’s dress, incorporating a loose fitting blouse with an ankle length skirt. The outfit was complemented by a distinctive lace jacket, with the most popular coloring being in blue and golds, and a simple red fez on top, although the fez was commonly switched out with a veil for church services and other formal social gatherings. This look later known as the “Marie Dress” would become incredibly popular among the women of Greece and could soon be seen from Athens to Belgrade and Ioannina to Constantinople. Other changes would take place including the incorporation of various luxury fabrics, materials, and colors into men and women's clothing that had been outlawed by the Ottoman Empire.

Typical Dress for Greek Men and Women during the Ottoman Era

Katarina Botsaris, daughter of Greek General Markos Botsaris wearing “Marie Dress”

Greek literature and writing also experienced a number of important developments during this period as the language debate came to the fore of Greek society. The Greek Language Debate was a protracted scholarly dispute regarding the official language of Greece. At the turn of the 19th century, two Greek dialects were in use, Demotic and Katharevousa. Demotic or dimotiki was a dialect of Greek spoken by the vast majority of the people of Greece and generally considered to be the natural evolution of Ancient Greek by its relatively few supporters. However, many Greek scholars, philosophers, and linguists considered it to be a bastardization of Ancient Greek that had been heavily corrupted by Turkish and other foreign languages. Katharevousa in comparison was considered a more faithful recreation of ancient Greek thus earning it the support of many intellectuals and influential Greeks.

Katharevousa also served as the official language of the Greek Government as it was considered nobler and more formal than the vulgar and crass Demotic Greek of the masses. This decision was generally well received by the legal experts, wealthy merchants, and educated class of Greek society, but it did cause problems with the general public who were generally illiterate and uneducated in most scholarly matters. Ioannis Kapodistrias' efforts to boost education throughout the country were relatively successful, albeit incredibly slow. Teaching was done almost exclusively in Katharevousa in a bid to help proliferate the language among the people. Ultimately, it was the hope of many Greek scholars and linguists that Katharevousa would serve as a stepping stone, rather than an end goal, between the lowly Demotic Greek and the nobler Ancient Greek.

Another important spreader of Katharevousa across Greece was literature and poetry, and of all the writers of the era, none championed Katharevousa more than the famous Greek poet Panagiotis Soutsos. In many ways, Panagiotis Soutsos was the Greek equivalent of Lord Byron, an exemplary poet of his time who certainly made his opinion known throughout his many works which were themselves extremely popular and influential among the people of Greece. By exclusively using Katharevousa in all of his works, Soutsos helped to proliferate the dialect across the country among his many readers. There were some problems that arose because of the Language Debate however.

While Katharevousa and Demotic were generally recognizable to one another there were several key differences and these differences unfortunately resulted in several clashes between the supporters of each. The most famous, or rather the most infamous incident surrounding the Greek Language Debate was the Agora Riots of 1847. Following a rendition of the play

Seven Against Thebes performed in Demotic, the crowd, which was primarily composed of Katharevousa supporters, attacked the actors, set fire to the theatre, and raged through the streets of Athens causing wanton destruction on their way towards the ancient Agora. The event was only halted by the quick intervention of the local authorities who swiftly surrounded and subdued the rioters any further harm could be done. Sadly, two individuals would lose their lives in the event and hundreds of Drachmae in damages had been incurred. Despite this embarrassment, Katharevousa would retain its popularity among the upper class of Greek society for years to come.

Next Time: A Window to the East

[1] Aside from the date, this is the same as OTL.

[2] The Walls of Mycenae were so tall and thick that many ancient Greeks believed they had been built by cyclopes, providing the walls with their distinctive name, the “Cyclopean Walls”. Cyclopean masonry is generally defined by the massive boulders and unworked stones that form the structure and are held together by their sheer weight and size rather than with mortar. Mycenae also features some examples of Ashlar masonry as well, with the Lion Gate being the best example of Ashlar masonry monument at the site.

[3] Lord Byron was extremely critical of Elgin’s removal of the Marbles from the Acropolis, going so far as to call him a vandal and a looter. He would even write about the event in one of his poems,

Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage in 1812.