Guys the solution to having an intertwined economy with an enemy isn't to try changing your economy to not be intertwined with the other country, but to make them not an enemy. Look at the difference in success between the Continental System and the European Economic Community.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pride Goes Before a Fall: A Revolutionary Greece Timeline

- Thread starter Earl Marshal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan LeagueThis may not be an option when your enemy is oppressing the ethnic group and religion that your nation is built on and contains vast amount of land your nation considers rightfully belonging to it.Guys the solution to having an intertwined economy with an enemy isn't to try changing your economy to not be intertwined with the other country, but to make them not an enemy.

Honestly ottoman Greek friendship is basically ASB at this point in time in history and probably for quite some time, indeed it’s only possible now because massive population exchanges and land annexation occurred and even then Cyprus is still a massive sore on geek/Turkish relations to this day.

Well to be honest is a greco-turco friendship is not impossible at some time ( look at cyprus pre 1955),but as you said right now that friendship is all but impossible....but when they have a more "natural border" things could get more friendlyThis may not be an option when your enemy is oppressing the ethnic group and religion that your nation is built on and contains vast amount of land your nation considers rightfully belonging to it.

Honestly ottoman Greek friendship is basically ASB at this point in time in history and probably for quite some time, indeed it’s only possible now because massive population exchanges and land annexation occurred and even then Cyprus is still a massive sore on geek/Turkish relations to this day.

Chapter 58: A Prelude to Revolution

Chapter 58: A Prelude to Revolution

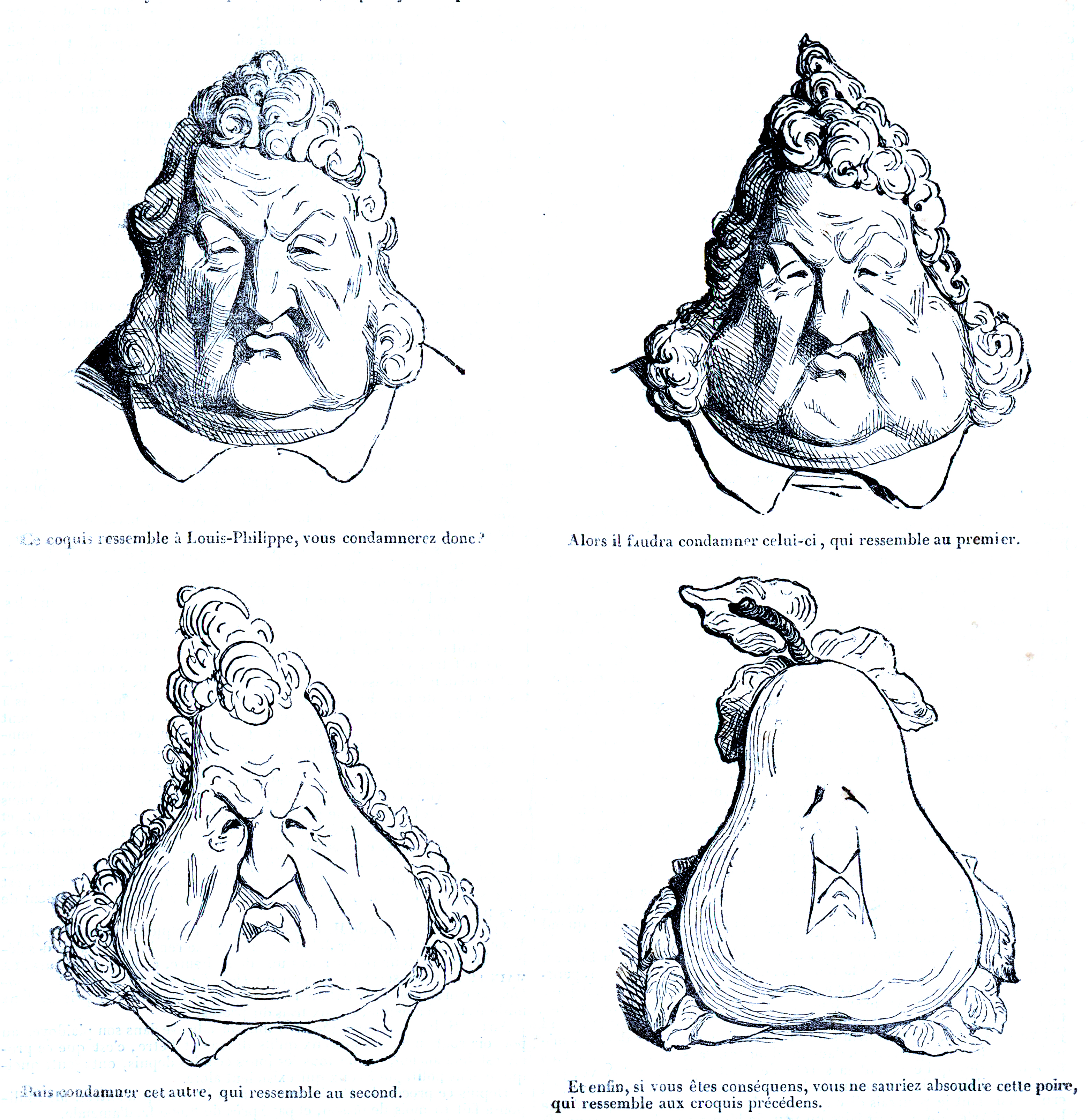

Louis-Philippe Becomes a Pear, a Political Cartoon Depicting the French King’s Declining Popularity

By the dawn of 1847, much of Europe had been at peace for the last 16 years as the states of Britain, France, Russia, Prussia, and Austria maintained an uneasy sense of stability over the continent. The failed uprisings of 1830 and 1831 had fallen short of their altruistic goals of liberalism, nationalism, and republicanism for all as they would only succeed in ousting the hated Bourbon dynasty in France, establishing a new constitution in Switzerland, and creating the new Kingdom of Belgium in the Low Countries. Most revolutionaries were rounded up and imprisoned in the aftermath of their revolts, whilst aristocrats and monarchs returned to the earlier status quo where they paid little concern for the wants and needs of the common folk. On the surface it would seem that this gilded age of absolutism and monarchism would continue unabated as it had for much of the last century, however, beneath the veneer there remained widespread unrest and dissatisfaction which grew with each passing year. Nowhere was this felt more so than in the Kingdom of France.

Having been ushered into power by a flurry of revolutionary fervor in late July 1830, the new King Louis-Philippe of the House of Orleans provided the common folk of France with the hope of a brighter future. He swore in his coronation oath that he would roll back King Charles X’s reactionary dictates, to begin much needed land reform, and to enact broad sweeping reforms to the French Government. He would abolish many of the old titles, honorifics, and privileges of the old Ancien Régime, even going as far as to modify his own title from “the King of France and Navarre” to “King of the French” in keeping with the old Constitution of 1791. Most, if not all of the July Ordinances were immediately repealed upon his ascension as were several of the more reactionary policies of the restored Bourbon Monarchy such as the use of capital punishment for those who slandered the Catholic church. Several Jacobins, Republicans, and Bonapartistes were permitted to return to France after several years in exile and Louis-Philippe would end the persecution of politics clubs across the country. For all these promises of liberal reforms, as well as his austere image as a bourgeoisie monarch, he was praised as "le Roi Citoyen" (the Citizen King). However, despite fulfilling many of his promises, the July Monarchy immediately faced immense perils from without and from within.

Although he was strongly opposed to the Ultra-Royalists policies of his Bourbon predecessors, and despite portraying himself as an avid liberal in his younger years and more recently as a champion of the liberal cause during the July Revolution; by the start of the 1830’s King Louis-Philippe was by all accounts a moderate conservative. This would bring him no shortage of trouble as the illegitimacy of his ascension in the eyes of French Conservatives earned him their undying hostility, and his efforts to avoid completely alienating the conservatives of French society only served to anger his liberal supporters whom he had relied upon to gain the throne in 1830. For all his good intentions the Legitimists (supporters of the "legitimate" Bourbon dynasty) would have none of it, as many in the French Government simply refused to accept King Louis-Philippe's authority over them, ultimately forcing him to purge them from Government entirely. They also charged him with the murder of the Ultra-Royalist Prince of Conde, who died shortly after the July Revolution under mysterious circumstances, although little evidence existed to support these allegations and the King was later cleared of all wrong doing.[1] Tensions between the two would worsen the following February, when a memorial service for the late Duc de Berry sparked a Legitimist protest against the ruling July Monarchy on the streets of Paris. The protests would soon escalate as counter protests by liberal groups descended upon the Legitimists and beat them to a bloody pulp. By far though the most infamous act of Legitimist opposition to the Orléanist Government was the Vendee Revolt of 1832.

In the Spring of 1832 the former Duchess of Berry, Princess Caroline de Bourbon returned to France seeking to push her son's claim for the French throne. Her arrival would bring many Legitimists to the Vendee where they would promptly instigate a revolt against the French Government. While the uprising would see several thousand supporters take up arms against the Orléanist Government, the July Monarchy quickly responded to the uprising by dispatching an army under the command of the renowned Republican General Jean Maximilien Lamarque. Lamarque and his force raced to Nantes where they would engage and then disperse the Legitimist rebels in short order, ending the rebellion in an instant. With the revolt a failure, the Duchess of Berry was forced to flee France once again never to return, effectively ending the Legitimist threat to King Louis-Philippe and the House of Orleans. However, as conflict with the Legitimists died down, conflict with the Republicans soon emerged.

Initially many on the political left gave the new king some degree of leniency in the hope he would follow through on his many promises to them, yet the new King's half measures left many Liberals disappointed. Nationalists were also dissatisfied by the new July Monarchy as King Louis-Philippe had promised French support to the Italian and Polish revolutionaries in their fights for independence, only to then betray them to their Austrian and Russian overlords who quickly quashed the revolutions in their lands. The Citizen King’s vehement refusal to abolish peerages and broaden suffrage to all men earned him the outrage of many Republicans across France, and his failure to appropriately deal with the Cholera epidemic which had settled over France resulted in frequent demonstrations by the afflicted Parisian populace outside Tuileries Palace. While tension was certainly high in Paris, it would only boil over following the death of the beloved Liberal General Lamarque in early June 1832 to Cholera.

General Jean Maximilien Lamarque was a respected figure in Parisian society having been a loyal Republican and Bonarpartiste in his younger years. He would also become one of the July Monarchy's most ardent critics in the French Parliament and the French press. Nevertheless, he remained a loyal Frenchmen who served his country and his people to the best of his abilities, causing him to develop quite the following among the poor and downtrodden across the country. His death to cholera on the 2nd of June 1832, however, would spark riots against the July Monarchy as many within the Parisian Mob believed the Government had killed their General out of jealousy and contempt.[2] By the night of June 6th, much of Paris was up in arms as several thousand Radical Liberals, Republicans, Jacobins, and Bonapartistes established blockades and barricades across the city and declared a revolution. Many revolutionaries wished to re-establish the old republic, while many more were simply angered by the Government's poor handling of the French economy, which had left hundreds of thousands of Frenchmen impoverished. For three days, the Parisian mob would wantonly destroy government buildings and burn the businesses of known merchants, tradesmen, and bankers (all men who were commonly regarded as being the King's closest supporters). They would attack Government ministers and even attempt to assault Tuileries Palace, before being pushed back by the National Guard.

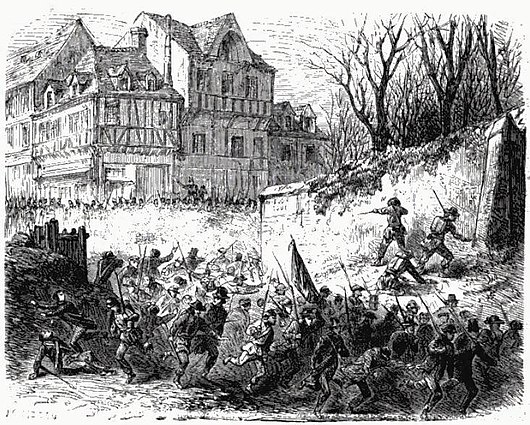

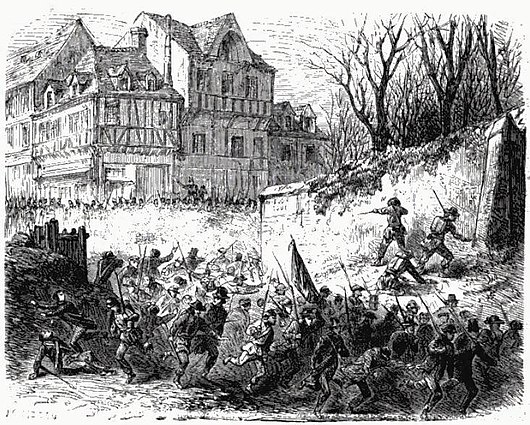

A Scene from the 1832 Paris Uprising

Although the death of General Lamarque had served to unite the Parisian Mob in opposition to the July Monarchy, it also deprived them of a capable leader and talented military commander who could turn their anger into something greater. Without a singular figure to coalesce around the revolutionaries would soon fall to infighting as they were divided on what to do should they succeed in their goals of toppling the July Monarchy. Their differences would unfortunately prove too great for them to overcome, leaving the would be revolutionaries an easy target for the French Army and National Guard who methodically quashed the uprising across the city and on the 9th of June the "revolution" was officially dead in Paris. Other uprisings would emerge in the cities of Lyon, Limoges, and Marseille among several others, but they too suffered from disorganized and internal division, and were soon dealt with. Nevertheless, protests and riots would continue across the country for some time, but for King Louis-Philippe he had weathered this dangerous storm relatively unscathed.

With the trials of 1832 behind them, the Orléanist Government was finally permitted a chance to breath thanks to a modest recovery in the French economy that began in the mid-1830’s. The good economic news would be followed soon after by the marriage of the King’s children to various princes, princesses, dukes, and duchesses across Europe. His eldest daughter Princess Louise would be married to her cousin, Prince Leopold of the Two Sicilies in January 1834, relieving the lingering tension between the two royal houses. The following November, his youngest daughter Princess Clementine would marry King Otto of Belgium bringing the Belgian kingdom into the French sphere through holy matrimony. His son and heir, Prince Ferdinand Philippe was married to the Duchess Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, a cousin of the King of Prussia Friedrich Wilhelm III and Queen Victoria of Britain in May 1837. Finally, his second daughter Princess Marie would marry Prince Alexander of Württemberg, a cousin of Queen Victoria of Britain and a nephew of King Leopold of Greece later that same year in October 1837. The French state also enjoyed success in its overseas ventures during this time as well.

In Algeria, local unrest had finally begun to die down in the colony after making peace with Emir Abdelkader in 1837 and the ensuing settlement of French citizens in the region began providing much needed dividends to the costly enterprise. Relations with Egypt continued to prove fruitful and beneficial to both parties, while a new relationship was forged with Persia in 1839 providing the French Arms Manufacturing industry with a constant source of demand. The French would also engage themselves in Mexico and Argentina as unrest in the two countries had unfortunately seen French citizens brought to harm. With the reluctant aid of the United States of America and the Republic of Texas, France was able to enforce a blockade on the troubled Centralist Republic of Mexico and force several concessions from them. Their efforts in Argentina while not nearly as successful, certainly demonstrated French power and influence in the region, helping to bolster their Great Power status throughout the South American continent.

Problems did exist for the French Court during this time as the July Monarchy's relationship with Great Britain was unfortunately very troubled. Rumors of British support for the Duchess of Berry's Vendee Revolt in 1832 would unfortunately sour relations between the two states during the early 1830's. While little evidence existed to perpetuate the Duchess of Berry's claims of British aid for her Legitimist uprising - aside from Canning's longtime friendship with King Charles X and a few interactions between Canning and the Duchess - the rumors themselves proved to be more than enough to scuttle any friendship between the two for some time. Matters would only worsen further in 1834 as the French Ambassador to Britain, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord would have a falling out with the interim British Prime Minister Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington over differing views for the Middle East and the Iberian Peninsula leading to Talleyrand’s resignation from the post in the Fall.[3] His replacement Louis-Mathieu Molé was not received well by the British public and his relationship with the new British Prime Minister Earl Grey, and by proxy France’s relationship with Britain, suffered as a result.

Relations between the two would suffer another blow following the Blockade of Mexico in late 1838/early1839 as Britain had sided alongside Mexico against the French and had mediated the dispute in Mexico's favor, but it would be the Second Syrian War and the coinciding Cyprus Affair which would see relations between the two Powers reach their lowest ebb since the Napoleonic Wars. France's support of the Khedivate of Egypt would unfortunately result in a clash between French and Ottoman ships off the coast of Cyprus in the Summer of 1840. France, seeking recompense, demanded the Ottomans make a number of humiliating concessions to them. The Ottomans, with British support refused, leading the French navy to enact a blockade around the island for over a month before they were forced to abandon the venture under threat of war by Britain. While the deterioration of relations with Britain were disappointing, a more concerning development to the Orléanist court were various reports indicating that the Duke of Reichstadt (Napoleon II) had survived the Battle of Pavia in 1831.

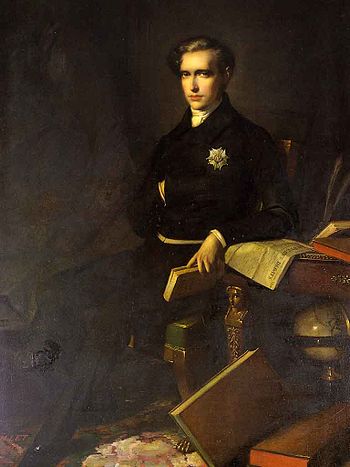

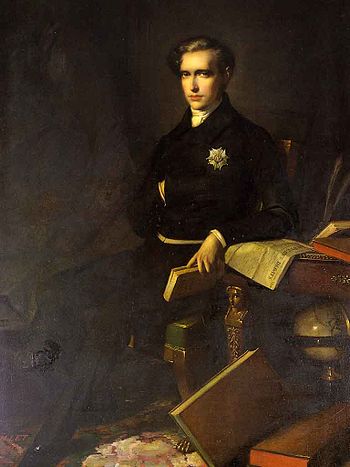

Napoleon II in 1840

Most had thought him dead, but the lack of a body as well as admissions of doubt by the Austrian Government, enabled rumors of Napoleon Franz's survival to persist long after that fateful day. In truth, young Franz was very much alive in the Swiss Canton of Thurgau where he lived alongside his two cousins, Charles-Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III) and Napoleon-Louis (Louis II of Holland). In the chaos of the Italian Uprising of 1830-1831, the Duke of Reichstadt had managed to elude his handlers and slip away into the Alps where he was soon joined by his cousins, their mother the Duchess of Saint-Leu, and a small band of loyal followers. During his time in Switzerland, young Franz enjoyed a quiet, but comfortable life as an officer in the Swiss Army, where he furthered his abilities as a leader of men and where he would learn of the plights of the common folk. His time in hiding would not last forever, as word of his survival would find its way out of Switzerland to his many allies and enemies. Beginning in late September 1835, his hated adversary Austrian Chancellor Metternich began dispatching agents into Switzerland seeking to reclaim the wayward Duke of Reichstadt by force if necessary. Having been granted a small taste of freedom after years in a gilded cage, Napoleon Franz refused to return to Vienna and chose instead to depart Europe for the Americas where he would remain for some time.

Traveling first to Brazil, Napoleon Franz would make his way to the United States of America where he would wine and dine with prominent businessmen and politicians from New York to Washington D.C. During his stay in the US, he would briefly visit his uncle Joseph's old manor Point Breeze in New Jersey, a place once renowned across America for its magnificent art gallery and picturesque gardens. His time in America was generally quiet however, filled with dinner parties and social events with socialites sympathetic to his plight. By the start of 1841, young Franz would choose to leave the Americas and return to Europe this time by way of Great Britain. In what was a great about-face from the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon II was well received by the British public and British Government who lauded him with praise and admiration compared to the hated and vilification they held for old King Louis-Philippe. During his stay in London, Napoleon Franz would meet with the young Queen Victoria who was instantly smitten by his kindness, his intelligence, and his charming demeanor and would develop a fond opinion of the young man. Despite traveling far and wide from Italy and Switzerland to the Americas and Great Britain, Napoleon Franz managed to keep a close tab on the events in France through his vast network of supporters and benefactors.

The exact extent to which Napoleon II was in contact with his followers in France is unknown, but it was clear that he was sending letters and aides across the border with some regularity. Several Bonapartistes had allegedly been seen meeting with the former French Emperor at his residence Chateau Arenenberg in Salenstein during his short stay there according to King Louis-Philippe's agents and talks of a coup against the Orléanist Government began to emerge. In fact, when word of the Eaglet's survival became common knowledge in France a series of disorderly uprisings would break out across the country in his favor, yet in spite of their great bravery and valor, the rebels were quickly subdued by forces loyal to the July Monarchy. Fearful that other Bonapartistes would rise in rebellion again at a later date, the French Government became increasingly paranoid and began cracking down on known Bonapartiste and Republican elements within the military and Government. Some officers were reassigned to Algiers or the Caribbean, while others were cashiered out of the military entirely; similarly the Government bureaucracy would also have several of its more radical actors removed from positions of power.

As the years progressed, the French Government began taking harsher measures against its adversaries as acts of violence and assassination attempts against them escalated. An attack on the king and his family in July 1835 would see several of King Louis-Philippe's closest aides killed while two of the King's sons, the Duke of Nemours and the Prince de Joinville, were injured in the attack. Several of the King's ministers and most vocal supporters were also targeted by militant Republicans in several plots over the years, resulting in the deaths of the President of the Council of State Amedee Girod de l'Ain in February 1838 and Finance Minister Georges Humann in June 1842 along with a few others all of which greatly destabilized the July Monarchy. Fortunately, most of these plots and plans ended in failure, resulting in the imprisonment of numerous conspirators and saboteurs, enabling the Orléanist Government to gradually consolidate its control over the country and by the end of 1844, the July Monarchy had successfully dealt with the most glaring threats to their regime. While the July Monarchy had done its best to calm the situation in France, matters outside of their control would quickly unravel all the work that King Louis-Philippe and his government had done to secure his family's hold on the French throne.

An Assassination Attempt on King Louis-Philippe on the Boulevard du Temple (1835)

Beginning in 1845, a terrible blight began afflicting potato harvests all across Europe from France and Britain to Austria and Russia. Although the crop made up a small portion of the average European’s diet its sudden absence from most groceries would see prices for all other food stuffs increase dramatically that year. The situation was even worse in France as their cereal harvests had been especially poor that same year leaving many thousands of French men and women to go hungry. Thousands would die of hunger in 1845, while many thousands more would go hungry leading anger to rapidly build against the Orléanist Government for failing to effectively combat the famine. The following year would see the potato blight continue unabated and that year’s grain harvest also ended in failure leading to frequent demonstrations outside Tuileries Palace. Growing tensions between the government and the people nearly sparked another revolution in France in 1846, as had occurred in both 1789 and 1830, and was only averted by the quick reaction of King Louis-Philippe and his government, authorizing the purchase of Ukrainian and Egyptian grain at a great expense.

The next year would bring a better grain harvest, alleviating some of the concerns for the French Government, but their relief was cut short as the French economy began experiencing signs of a deepening recession. The cost for regular goods continued to skyrocket with some prices rising nearly 150% from their price in 1844, demand for goods plummeted, wages decreased dramatically with some losing nearly 30% of their incomes, and unemployment ballooned above 25% of the labor force. In Paris alone, nearly 200,000 men were without regular work, while another 100,000 were day laborers who worked for scraps.[4] Sadly, the economic recession did not stop at the French borders as every European Country from Portugal to Greece experienced some degree of economic hardship.

Perhaps one country that had endured hardships just as great as France was the neighboring Kingdom of Belgium whose short life had been nothing but turmoil and unrest.

Like France and the rest of Europe, Belgium suffered through the terrible famines of 1845 and 1846 and the economic collapse that followed it. Many were suffering from widespread starvation and hunger, leading to bread riots on a regular basis in the streets of Brussels. The Belgian metallurgy industry declined by as much as 50% between 1845 and 1848, while Belgian linen exports declined by two thirds because of the dominance of cheaper British textiles on the market. Numerous businesses and enterprises were bankrupted, while thousands were left unemployed and homeless. It was a difficult situation for any country to handle, and yet it was made worse by the inadequate leadership of King Otto and the Belgian Government.

Prince Otto of Bavaria had ascended to the throne of Belgium in the Spring of 1831 following his election at the hands of the Second Belgian National Congress, yet his rule would be troubled from the start. Due to his age, the King required a regency to rule in his name until his majority, a regency which many Belgian Liberals hoped would be directed by men like themselves who would sway their young sovereign towards their ideals of a constitutional monarchy. Sadly, their efforts would be confounded by the young King's regency would be comprised primarily of Bavarians who favored the rights of kings over the rights of man. They vehemently defended their sovereigns' powers and privileges, and would even attempt to expand upon them where they were able. Due to their foreignness as well as their tyrannical nature, they developed a poor reputation among the people of Belgium who came to despise and hate them. Otto would disappoint Belgian Liberals once again when he reached his majority in June 1835, as he chose to retain the services of his former regents in his Government much to the displeasure of his subjects. He would also exhibit many of the absolutist tendencies that the people of Belgium had opposed in their former King, King William I of the Netherlands and would unfortunately lead to conflict between the Belgian Parliament and the Belgian Monarchy. Despite these disappointments, hope for the monarchy would be rekindled upon the announcement of King Otto's engagement to Princess Clementine of France.

Princess Clementine of France

King Otto's marriage to the young Princess Clementine of France in November 1835 aided his cause immensely as he could now attach himself directly to his primary benefactor, King Louis-Philippe through marriage. Sadly though, their union would be a troubled one. Although the new Belgian Queen was certainly agreeable to the Belgian King and the Belgian court, she would prove unable to provide a male heir for the dynasty leaving its future in doubt. In 1837 her first pregnancy would sadly end in a stillbirth of a baby boy, causing the couple great suffering and heartache. Two years later in 1839, the Queen would give to a girl, whom the King and Queen named Maria Amelia after Clementine’s mother, yet tragedy would strike once again as young Maria Amelia was born sickly and frail, and by year's end she was dead. A third attempt at a child would result in another daughter, named Clotilde in 1842 who would be the only child of Otto and Clementine to survive childhood. Unfortunately for Otto and Clementine, the birthing process for Princess Clotilde had left the young Queen terribly weak and unwell forcing the royal couple to effectively abandoned any plans for any further children. While Otto would still care for Clementine, his affection for her waned over the years leading him to attract several mistresses with whom he allegedly had several children leading to unrest in the King's household. Unrest would also emerge between Belgium and its allies thanks in no small part to the misguided efforts of King Otto.

In 1832, the Belgian Government at the request of France, began the complete demolition of the Barrier, a system of forts along the border between Belgium and France that had been established by the Duke of Wellington following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. French soldiers would also be permitted to garrison several fortresses along the border with the Netherlands, as Dutch soldiers frequently raided the frontier between Belgium and the Netherlands and the Belgian Army had proven incapable of stopping them. These moves by the Belgian Government, combined with King Otto's apparent closeness with King Louis-Philippe sparked fears in both Amsterdam and London of a growing French influence over the region which unfortunately alienated any allies Otto and the Belgian Government might have had in Westminster. Britain for their part was not blameless in the deterioration of relations between themselves and little Belgium as their mechanized textile industry effectively bankrupted the Belgian linen industry. As cheaper British goods flooded across the Channel, Belgian wares lost much of their value resulting in soaring unemployment and rising impoverishment which only served to aggravate matters between them even further.

While Otto was certainly earnest in his efforts to aid his country, his constant interference into the matters of the Parliament and his frequent disregard of the Belgian Constitution earned him the vilification of the Belgian political class. His rule was becoming increasingly reliant upon the support of the conservative Catholic Party who generally tolerated his absolutism more than their hated rival, the Liberal Party who were more pronounced in their opposition to Otto's governance. For most matters, Otto was able to simply push his initiatives through with the support of Catholic votes alone, but as the years progressed, the Liberals began gaining seats in Parliament in far greater numbers than the Catholics, and after the 1846 elections they would hold a clear majority in the Legislature much to the King's dismay. The lack of a clear heir, combined with the poor Belgian economy certainly didn't help Otto's standing among the Belgian politcal class, nor the people of Belgian. More detrimental to Otto, however, was his apparent inability to deal with Belgium’s neighbor to the North, the Kingdom of the Netherlands whose continued hostility remained a constant burden for Belgium.

Although the Kingdom of the Netherlands had been driven from Belgium following the Revolution in 1830, King William I of the Netherlands obstinately refused to accept the 1831 Treaty of London establishing Belgium as an independent country. His soldiers frequently skirmished with Belgian troops, if only to reaffirm his claim to the Southern Provinces, and he barred all Belgian ships from Dutch ports both in Europe and in his overseas territories which was incredibly damaging to the Belgian economy. Moreover, he continually ginned up unrest and agitation in the regions of Flanders against the increasingly French and Walloon dominated Belgian Government. However, this act of sedition was surprisingly mitigated somewhat by King Otto who travel the Belgian countryside visiting various Flemish communities in an attempt to foster good will between the people and the crown.

Sadly, these acts would do little to resolve the differences between the Walloons and the Flemish who had failed to develop a united national identity since achieving their independence in 1831. The Flemish had been unwilling partners of the Walloons in the Revolution, only being tied to the new state by the efforts of Walloon revolutionaries and French soldiers in the war against the Netherlands and were effectively treated as second class citizens by the ruling Walloon elite in Belgium. Persecution of Flemish communities by their Walloon neighbors both during and after the revolution would see many homes burnt to the ground, many businesses ruined, and many families left to fend for themselves. Between the destruction of the Revolution and the persecution by the Walloon controlled government, Flanders would become an impoverished shadow of its former self as wealth was directed to the north to the South of the country rather than the North. The city of Antwerp, once the jewel of the Southern Provinces had been reduced to a burnt out shell thanks to the prolonged siege of the city by the French army in 1831 and the lackluster recovery effort by the Belgian Government had done little to aid the city's inhabitants. This poverty in the North of the country would worsen dramatically following the famines of 1845-1846 and the economic recession of 1847.

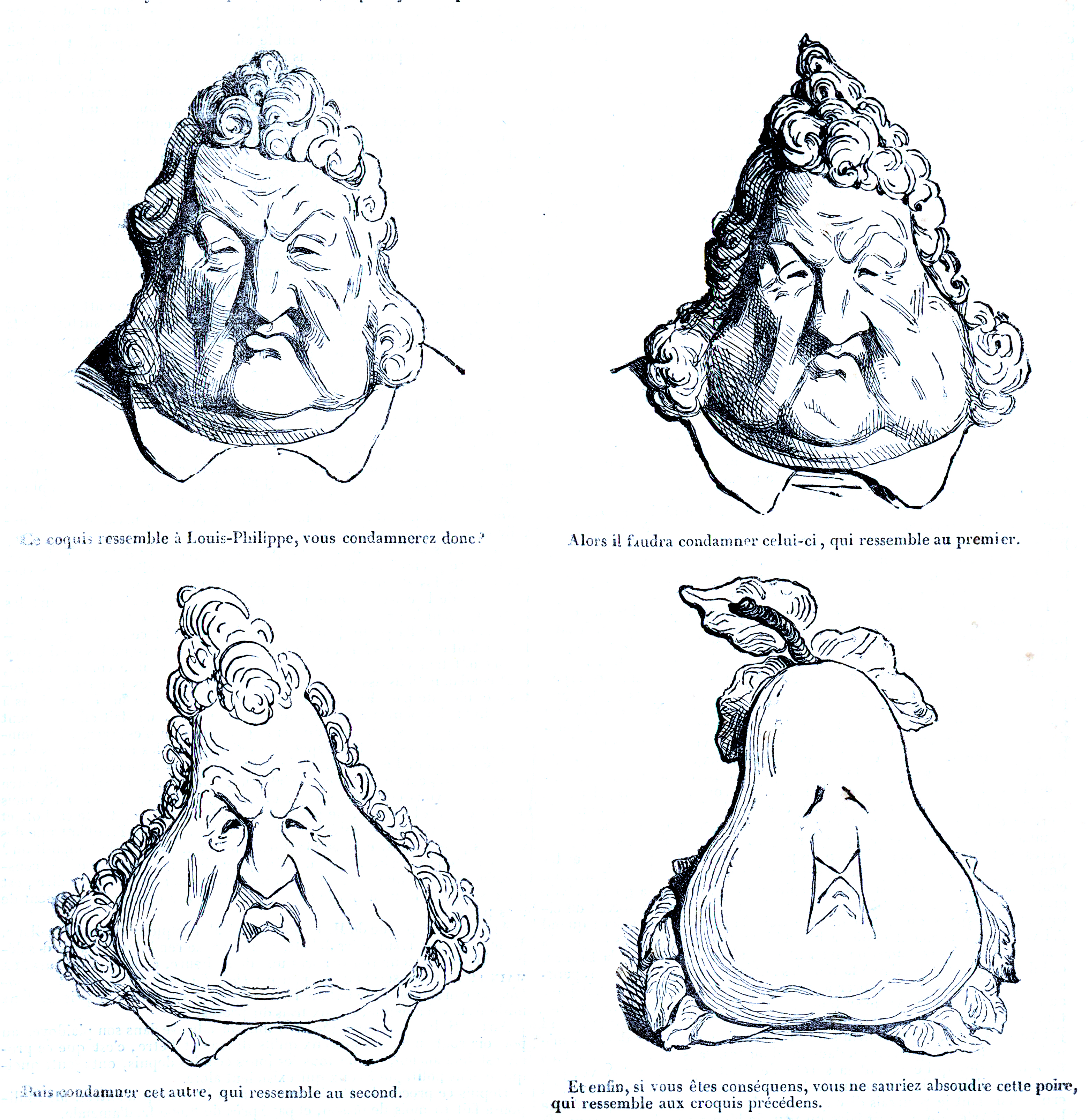

The Belgian Military Attacks the Flemings

Radical ideas of republicanism and socialism began making broad inroads into both Flanders and Wallonia leading many to openly protest the Monarchy and Belgian Government. Protests and riots began occurring in greater frequency, while the Legislature did little to resolve the growing unrest in Flanders. Surprisingly, it would be King Otto who acted first to deal with the issue. In what was to be King Otto's finest act, but also his most foolish, he unanimously declared that the Belgian Government would begin issuing and accepting the usage of both Dutch and French in all official paperwork, public laws and Royal orders. While this decision was generally applauded by the Flemish intellectual community; it was overwhelmingly denounced by the Walloons and Belgian Parliament as an act of tyranny. Protests would soon appear on the streets of Charleroi, Namur, Tournai, and numerous other Walloon towns and villages condemning the Monarchy. When the protests finally reached Brussels in early September while King Otto and his family were away visiting the town of Bastonge, the Belgian Parliament made its move against King Otto with the support of the Belgian Army. Staging an impromptu vote of no confidence in the continuation of the present monarchy, the Legislature voted to remove King Otto from power by a relatively wide margin as most of the Fleming Legislators had boycotted the event in opposition.

When it became clear that the people and the army were against him, Otto, upon the advice of his in-laws, agreed not to resist the will of the people and crossed the border into France. Despite leaving his Kingdom, Otto refused to accept his deposition under the vain hope that his people would see the error of their ways and call for his return. Sadly for the one time Belgian King, no such call would ever happen, and with that the reign of King Otto had come to an end. Little did anyone know, the events in Belgium on the 3rd of September 1847 would spark a far greater calamity that would scar Europe for generations to come.

Next Time: The Second Belgian Revolution

[1] The Prince of Conde’s son had been killed during the Napoleonic wars leaving him without an heir of his body, as such he named his godson, Prince Henri, son of Louis-Philippe as his legal heir. Legitimists believed that Conde was contemplating fleeing to Britain alongside the Bourbons after the July Revolution, effectively disinheriting Prince Henri, the Duke of Aumale. Seeking to preserve his son’s inheritance, the Legitimists argued that King Louis-Philippe had had Conde murdered. While the case would go to trial, no incriminating evidence was discovered, and the Prince’s death was ruled a suicide in an apparent act of autoerotic asphyxiation.

[2] The manner in which cholera was spread was still relatively unknown in the 1820’s and 1830’s, leading many people to believe that it was a poison. So in effect, many Parisians believed that General Lamarque had been murdered by the July Monarchy who were jealous of their beloved general.

[3] France was forced into joining the Quadruple Alliance by a fait-accompli from the British.

[4] For reference, the population of Paris was just above 900,000 people at the time of the 1848 Revolutions.

Louis-Philippe Becomes a Pear, a Political Cartoon Depicting the French King’s Declining Popularity

By the dawn of 1847, much of Europe had been at peace for the last 16 years as the states of Britain, France, Russia, Prussia, and Austria maintained an uneasy sense of stability over the continent. The failed uprisings of 1830 and 1831 had fallen short of their altruistic goals of liberalism, nationalism, and republicanism for all as they would only succeed in ousting the hated Bourbon dynasty in France, establishing a new constitution in Switzerland, and creating the new Kingdom of Belgium in the Low Countries. Most revolutionaries were rounded up and imprisoned in the aftermath of their revolts, whilst aristocrats and monarchs returned to the earlier status quo where they paid little concern for the wants and needs of the common folk. On the surface it would seem that this gilded age of absolutism and monarchism would continue unabated as it had for much of the last century, however, beneath the veneer there remained widespread unrest and dissatisfaction which grew with each passing year. Nowhere was this felt more so than in the Kingdom of France.

Having been ushered into power by a flurry of revolutionary fervor in late July 1830, the new King Louis-Philippe of the House of Orleans provided the common folk of France with the hope of a brighter future. He swore in his coronation oath that he would roll back King Charles X’s reactionary dictates, to begin much needed land reform, and to enact broad sweeping reforms to the French Government. He would abolish many of the old titles, honorifics, and privileges of the old Ancien Régime, even going as far as to modify his own title from “the King of France and Navarre” to “King of the French” in keeping with the old Constitution of 1791. Most, if not all of the July Ordinances were immediately repealed upon his ascension as were several of the more reactionary policies of the restored Bourbon Monarchy such as the use of capital punishment for those who slandered the Catholic church. Several Jacobins, Republicans, and Bonapartistes were permitted to return to France after several years in exile and Louis-Philippe would end the persecution of politics clubs across the country. For all these promises of liberal reforms, as well as his austere image as a bourgeoisie monarch, he was praised as "le Roi Citoyen" (the Citizen King). However, despite fulfilling many of his promises, the July Monarchy immediately faced immense perils from without and from within.

Although he was strongly opposed to the Ultra-Royalists policies of his Bourbon predecessors, and despite portraying himself as an avid liberal in his younger years and more recently as a champion of the liberal cause during the July Revolution; by the start of the 1830’s King Louis-Philippe was by all accounts a moderate conservative. This would bring him no shortage of trouble as the illegitimacy of his ascension in the eyes of French Conservatives earned him their undying hostility, and his efforts to avoid completely alienating the conservatives of French society only served to anger his liberal supporters whom he had relied upon to gain the throne in 1830. For all his good intentions the Legitimists (supporters of the "legitimate" Bourbon dynasty) would have none of it, as many in the French Government simply refused to accept King Louis-Philippe's authority over them, ultimately forcing him to purge them from Government entirely. They also charged him with the murder of the Ultra-Royalist Prince of Conde, who died shortly after the July Revolution under mysterious circumstances, although little evidence existed to support these allegations and the King was later cleared of all wrong doing.[1] Tensions between the two would worsen the following February, when a memorial service for the late Duc de Berry sparked a Legitimist protest against the ruling July Monarchy on the streets of Paris. The protests would soon escalate as counter protests by liberal groups descended upon the Legitimists and beat them to a bloody pulp. By far though the most infamous act of Legitimist opposition to the Orléanist Government was the Vendee Revolt of 1832.

In the Spring of 1832 the former Duchess of Berry, Princess Caroline de Bourbon returned to France seeking to push her son's claim for the French throne. Her arrival would bring many Legitimists to the Vendee where they would promptly instigate a revolt against the French Government. While the uprising would see several thousand supporters take up arms against the Orléanist Government, the July Monarchy quickly responded to the uprising by dispatching an army under the command of the renowned Republican General Jean Maximilien Lamarque. Lamarque and his force raced to Nantes where they would engage and then disperse the Legitimist rebels in short order, ending the rebellion in an instant. With the revolt a failure, the Duchess of Berry was forced to flee France once again never to return, effectively ending the Legitimist threat to King Louis-Philippe and the House of Orleans. However, as conflict with the Legitimists died down, conflict with the Republicans soon emerged.

Initially many on the political left gave the new king some degree of leniency in the hope he would follow through on his many promises to them, yet the new King's half measures left many Liberals disappointed. Nationalists were also dissatisfied by the new July Monarchy as King Louis-Philippe had promised French support to the Italian and Polish revolutionaries in their fights for independence, only to then betray them to their Austrian and Russian overlords who quickly quashed the revolutions in their lands. The Citizen King’s vehement refusal to abolish peerages and broaden suffrage to all men earned him the outrage of many Republicans across France, and his failure to appropriately deal with the Cholera epidemic which had settled over France resulted in frequent demonstrations by the afflicted Parisian populace outside Tuileries Palace. While tension was certainly high in Paris, it would only boil over following the death of the beloved Liberal General Lamarque in early June 1832 to Cholera.

General Jean Maximilien Lamarque was a respected figure in Parisian society having been a loyal Republican and Bonarpartiste in his younger years. He would also become one of the July Monarchy's most ardent critics in the French Parliament and the French press. Nevertheless, he remained a loyal Frenchmen who served his country and his people to the best of his abilities, causing him to develop quite the following among the poor and downtrodden across the country. His death to cholera on the 2nd of June 1832, however, would spark riots against the July Monarchy as many within the Parisian Mob believed the Government had killed their General out of jealousy and contempt.[2] By the night of June 6th, much of Paris was up in arms as several thousand Radical Liberals, Republicans, Jacobins, and Bonapartistes established blockades and barricades across the city and declared a revolution. Many revolutionaries wished to re-establish the old republic, while many more were simply angered by the Government's poor handling of the French economy, which had left hundreds of thousands of Frenchmen impoverished. For three days, the Parisian mob would wantonly destroy government buildings and burn the businesses of known merchants, tradesmen, and bankers (all men who were commonly regarded as being the King's closest supporters). They would attack Government ministers and even attempt to assault Tuileries Palace, before being pushed back by the National Guard.

A Scene from the 1832 Paris Uprising

Although the death of General Lamarque had served to unite the Parisian Mob in opposition to the July Monarchy, it also deprived them of a capable leader and talented military commander who could turn their anger into something greater. Without a singular figure to coalesce around the revolutionaries would soon fall to infighting as they were divided on what to do should they succeed in their goals of toppling the July Monarchy. Their differences would unfortunately prove too great for them to overcome, leaving the would be revolutionaries an easy target for the French Army and National Guard who methodically quashed the uprising across the city and on the 9th of June the "revolution" was officially dead in Paris. Other uprisings would emerge in the cities of Lyon, Limoges, and Marseille among several others, but they too suffered from disorganized and internal division, and were soon dealt with. Nevertheless, protests and riots would continue across the country for some time, but for King Louis-Philippe he had weathered this dangerous storm relatively unscathed.

With the trials of 1832 behind them, the Orléanist Government was finally permitted a chance to breath thanks to a modest recovery in the French economy that began in the mid-1830’s. The good economic news would be followed soon after by the marriage of the King’s children to various princes, princesses, dukes, and duchesses across Europe. His eldest daughter Princess Louise would be married to her cousin, Prince Leopold of the Two Sicilies in January 1834, relieving the lingering tension between the two royal houses. The following November, his youngest daughter Princess Clementine would marry King Otto of Belgium bringing the Belgian kingdom into the French sphere through holy matrimony. His son and heir, Prince Ferdinand Philippe was married to the Duchess Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, a cousin of the King of Prussia Friedrich Wilhelm III and Queen Victoria of Britain in May 1837. Finally, his second daughter Princess Marie would marry Prince Alexander of Württemberg, a cousin of Queen Victoria of Britain and a nephew of King Leopold of Greece later that same year in October 1837. The French state also enjoyed success in its overseas ventures during this time as well.

In Algeria, local unrest had finally begun to die down in the colony after making peace with Emir Abdelkader in 1837 and the ensuing settlement of French citizens in the region began providing much needed dividends to the costly enterprise. Relations with Egypt continued to prove fruitful and beneficial to both parties, while a new relationship was forged with Persia in 1839 providing the French Arms Manufacturing industry with a constant source of demand. The French would also engage themselves in Mexico and Argentina as unrest in the two countries had unfortunately seen French citizens brought to harm. With the reluctant aid of the United States of America and the Republic of Texas, France was able to enforce a blockade on the troubled Centralist Republic of Mexico and force several concessions from them. Their efforts in Argentina while not nearly as successful, certainly demonstrated French power and influence in the region, helping to bolster their Great Power status throughout the South American continent.

Problems did exist for the French Court during this time as the July Monarchy's relationship with Great Britain was unfortunately very troubled. Rumors of British support for the Duchess of Berry's Vendee Revolt in 1832 would unfortunately sour relations between the two states during the early 1830's. While little evidence existed to perpetuate the Duchess of Berry's claims of British aid for her Legitimist uprising - aside from Canning's longtime friendship with King Charles X and a few interactions between Canning and the Duchess - the rumors themselves proved to be more than enough to scuttle any friendship between the two for some time. Matters would only worsen further in 1834 as the French Ambassador to Britain, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord would have a falling out with the interim British Prime Minister Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington over differing views for the Middle East and the Iberian Peninsula leading to Talleyrand’s resignation from the post in the Fall.[3] His replacement Louis-Mathieu Molé was not received well by the British public and his relationship with the new British Prime Minister Earl Grey, and by proxy France’s relationship with Britain, suffered as a result.

Relations between the two would suffer another blow following the Blockade of Mexico in late 1838/early1839 as Britain had sided alongside Mexico against the French and had mediated the dispute in Mexico's favor, but it would be the Second Syrian War and the coinciding Cyprus Affair which would see relations between the two Powers reach their lowest ebb since the Napoleonic Wars. France's support of the Khedivate of Egypt would unfortunately result in a clash between French and Ottoman ships off the coast of Cyprus in the Summer of 1840. France, seeking recompense, demanded the Ottomans make a number of humiliating concessions to them. The Ottomans, with British support refused, leading the French navy to enact a blockade around the island for over a month before they were forced to abandon the venture under threat of war by Britain. While the deterioration of relations with Britain were disappointing, a more concerning development to the Orléanist court were various reports indicating that the Duke of Reichstadt (Napoleon II) had survived the Battle of Pavia in 1831.

Napoleon II in 1840

Traveling first to Brazil, Napoleon Franz would make his way to the United States of America where he would wine and dine with prominent businessmen and politicians from New York to Washington D.C. During his stay in the US, he would briefly visit his uncle Joseph's old manor Point Breeze in New Jersey, a place once renowned across America for its magnificent art gallery and picturesque gardens. His time in America was generally quiet however, filled with dinner parties and social events with socialites sympathetic to his plight. By the start of 1841, young Franz would choose to leave the Americas and return to Europe this time by way of Great Britain. In what was a great about-face from the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon II was well received by the British public and British Government who lauded him with praise and admiration compared to the hated and vilification they held for old King Louis-Philippe. During his stay in London, Napoleon Franz would meet with the young Queen Victoria who was instantly smitten by his kindness, his intelligence, and his charming demeanor and would develop a fond opinion of the young man. Despite traveling far and wide from Italy and Switzerland to the Americas and Great Britain, Napoleon Franz managed to keep a close tab on the events in France through his vast network of supporters and benefactors.

The exact extent to which Napoleon II was in contact with his followers in France is unknown, but it was clear that he was sending letters and aides across the border with some regularity. Several Bonapartistes had allegedly been seen meeting with the former French Emperor at his residence Chateau Arenenberg in Salenstein during his short stay there according to King Louis-Philippe's agents and talks of a coup against the Orléanist Government began to emerge. In fact, when word of the Eaglet's survival became common knowledge in France a series of disorderly uprisings would break out across the country in his favor, yet in spite of their great bravery and valor, the rebels were quickly subdued by forces loyal to the July Monarchy. Fearful that other Bonapartistes would rise in rebellion again at a later date, the French Government became increasingly paranoid and began cracking down on known Bonapartiste and Republican elements within the military and Government. Some officers were reassigned to Algiers or the Caribbean, while others were cashiered out of the military entirely; similarly the Government bureaucracy would also have several of its more radical actors removed from positions of power.

As the years progressed, the French Government began taking harsher measures against its adversaries as acts of violence and assassination attempts against them escalated. An attack on the king and his family in July 1835 would see several of King Louis-Philippe's closest aides killed while two of the King's sons, the Duke of Nemours and the Prince de Joinville, were injured in the attack. Several of the King's ministers and most vocal supporters were also targeted by militant Republicans in several plots over the years, resulting in the deaths of the President of the Council of State Amedee Girod de l'Ain in February 1838 and Finance Minister Georges Humann in June 1842 along with a few others all of which greatly destabilized the July Monarchy. Fortunately, most of these plots and plans ended in failure, resulting in the imprisonment of numerous conspirators and saboteurs, enabling the Orléanist Government to gradually consolidate its control over the country and by the end of 1844, the July Monarchy had successfully dealt with the most glaring threats to their regime. While the July Monarchy had done its best to calm the situation in France, matters outside of their control would quickly unravel all the work that King Louis-Philippe and his government had done to secure his family's hold on the French throne.

An Assassination Attempt on King Louis-Philippe on the Boulevard du Temple (1835)

Beginning in 1845, a terrible blight began afflicting potato harvests all across Europe from France and Britain to Austria and Russia. Although the crop made up a small portion of the average European’s diet its sudden absence from most groceries would see prices for all other food stuffs increase dramatically that year. The situation was even worse in France as their cereal harvests had been especially poor that same year leaving many thousands of French men and women to go hungry. Thousands would die of hunger in 1845, while many thousands more would go hungry leading anger to rapidly build against the Orléanist Government for failing to effectively combat the famine. The following year would see the potato blight continue unabated and that year’s grain harvest also ended in failure leading to frequent demonstrations outside Tuileries Palace. Growing tensions between the government and the people nearly sparked another revolution in France in 1846, as had occurred in both 1789 and 1830, and was only averted by the quick reaction of King Louis-Philippe and his government, authorizing the purchase of Ukrainian and Egyptian grain at a great expense.

The next year would bring a better grain harvest, alleviating some of the concerns for the French Government, but their relief was cut short as the French economy began experiencing signs of a deepening recession. The cost for regular goods continued to skyrocket with some prices rising nearly 150% from their price in 1844, demand for goods plummeted, wages decreased dramatically with some losing nearly 30% of their incomes, and unemployment ballooned above 25% of the labor force. In Paris alone, nearly 200,000 men were without regular work, while another 100,000 were day laborers who worked for scraps.[4] Sadly, the economic recession did not stop at the French borders as every European Country from Portugal to Greece experienced some degree of economic hardship.

Perhaps one country that had endured hardships just as great as France was the neighboring Kingdom of Belgium whose short life had been nothing but turmoil and unrest.

Like France and the rest of Europe, Belgium suffered through the terrible famines of 1845 and 1846 and the economic collapse that followed it. Many were suffering from widespread starvation and hunger, leading to bread riots on a regular basis in the streets of Brussels. The Belgian metallurgy industry declined by as much as 50% between 1845 and 1848, while Belgian linen exports declined by two thirds because of the dominance of cheaper British textiles on the market. Numerous businesses and enterprises were bankrupted, while thousands were left unemployed and homeless. It was a difficult situation for any country to handle, and yet it was made worse by the inadequate leadership of King Otto and the Belgian Government.

Prince Otto of Bavaria had ascended to the throne of Belgium in the Spring of 1831 following his election at the hands of the Second Belgian National Congress, yet his rule would be troubled from the start. Due to his age, the King required a regency to rule in his name until his majority, a regency which many Belgian Liberals hoped would be directed by men like themselves who would sway their young sovereign towards their ideals of a constitutional monarchy. Sadly, their efforts would be confounded by the young King's regency would be comprised primarily of Bavarians who favored the rights of kings over the rights of man. They vehemently defended their sovereigns' powers and privileges, and would even attempt to expand upon them where they were able. Due to their foreignness as well as their tyrannical nature, they developed a poor reputation among the people of Belgium who came to despise and hate them. Otto would disappoint Belgian Liberals once again when he reached his majority in June 1835, as he chose to retain the services of his former regents in his Government much to the displeasure of his subjects. He would also exhibit many of the absolutist tendencies that the people of Belgium had opposed in their former King, King William I of the Netherlands and would unfortunately lead to conflict between the Belgian Parliament and the Belgian Monarchy. Despite these disappointments, hope for the monarchy would be rekindled upon the announcement of King Otto's engagement to Princess Clementine of France.

Princess Clementine of France

King Otto's marriage to the young Princess Clementine of France in November 1835 aided his cause immensely as he could now attach himself directly to his primary benefactor, King Louis-Philippe through marriage. Sadly though, their union would be a troubled one. Although the new Belgian Queen was certainly agreeable to the Belgian King and the Belgian court, she would prove unable to provide a male heir for the dynasty leaving its future in doubt. In 1837 her first pregnancy would sadly end in a stillbirth of a baby boy, causing the couple great suffering and heartache. Two years later in 1839, the Queen would give to a girl, whom the King and Queen named Maria Amelia after Clementine’s mother, yet tragedy would strike once again as young Maria Amelia was born sickly and frail, and by year's end she was dead. A third attempt at a child would result in another daughter, named Clotilde in 1842 who would be the only child of Otto and Clementine to survive childhood. Unfortunately for Otto and Clementine, the birthing process for Princess Clotilde had left the young Queen terribly weak and unwell forcing the royal couple to effectively abandoned any plans for any further children. While Otto would still care for Clementine, his affection for her waned over the years leading him to attract several mistresses with whom he allegedly had several children leading to unrest in the King's household. Unrest would also emerge between Belgium and its allies thanks in no small part to the misguided efforts of King Otto.

In 1832, the Belgian Government at the request of France, began the complete demolition of the Barrier, a system of forts along the border between Belgium and France that had been established by the Duke of Wellington following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. French soldiers would also be permitted to garrison several fortresses along the border with the Netherlands, as Dutch soldiers frequently raided the frontier between Belgium and the Netherlands and the Belgian Army had proven incapable of stopping them. These moves by the Belgian Government, combined with King Otto's apparent closeness with King Louis-Philippe sparked fears in both Amsterdam and London of a growing French influence over the region which unfortunately alienated any allies Otto and the Belgian Government might have had in Westminster. Britain for their part was not blameless in the deterioration of relations between themselves and little Belgium as their mechanized textile industry effectively bankrupted the Belgian linen industry. As cheaper British goods flooded across the Channel, Belgian wares lost much of their value resulting in soaring unemployment and rising impoverishment which only served to aggravate matters between them even further.

While Otto was certainly earnest in his efforts to aid his country, his constant interference into the matters of the Parliament and his frequent disregard of the Belgian Constitution earned him the vilification of the Belgian political class. His rule was becoming increasingly reliant upon the support of the conservative Catholic Party who generally tolerated his absolutism more than their hated rival, the Liberal Party who were more pronounced in their opposition to Otto's governance. For most matters, Otto was able to simply push his initiatives through with the support of Catholic votes alone, but as the years progressed, the Liberals began gaining seats in Parliament in far greater numbers than the Catholics, and after the 1846 elections they would hold a clear majority in the Legislature much to the King's dismay. The lack of a clear heir, combined with the poor Belgian economy certainly didn't help Otto's standing among the Belgian politcal class, nor the people of Belgian. More detrimental to Otto, however, was his apparent inability to deal with Belgium’s neighbor to the North, the Kingdom of the Netherlands whose continued hostility remained a constant burden for Belgium.

Although the Kingdom of the Netherlands had been driven from Belgium following the Revolution in 1830, King William I of the Netherlands obstinately refused to accept the 1831 Treaty of London establishing Belgium as an independent country. His soldiers frequently skirmished with Belgian troops, if only to reaffirm his claim to the Southern Provinces, and he barred all Belgian ships from Dutch ports both in Europe and in his overseas territories which was incredibly damaging to the Belgian economy. Moreover, he continually ginned up unrest and agitation in the regions of Flanders against the increasingly French and Walloon dominated Belgian Government. However, this act of sedition was surprisingly mitigated somewhat by King Otto who travel the Belgian countryside visiting various Flemish communities in an attempt to foster good will between the people and the crown.

Sadly, these acts would do little to resolve the differences between the Walloons and the Flemish who had failed to develop a united national identity since achieving their independence in 1831. The Flemish had been unwilling partners of the Walloons in the Revolution, only being tied to the new state by the efforts of Walloon revolutionaries and French soldiers in the war against the Netherlands and were effectively treated as second class citizens by the ruling Walloon elite in Belgium. Persecution of Flemish communities by their Walloon neighbors both during and after the revolution would see many homes burnt to the ground, many businesses ruined, and many families left to fend for themselves. Between the destruction of the Revolution and the persecution by the Walloon controlled government, Flanders would become an impoverished shadow of its former self as wealth was directed to the north to the South of the country rather than the North. The city of Antwerp, once the jewel of the Southern Provinces had been reduced to a burnt out shell thanks to the prolonged siege of the city by the French army in 1831 and the lackluster recovery effort by the Belgian Government had done little to aid the city's inhabitants. This poverty in the North of the country would worsen dramatically following the famines of 1845-1846 and the economic recession of 1847.

The Belgian Military Attacks the Flemings

When it became clear that the people and the army were against him, Otto, upon the advice of his in-laws, agreed not to resist the will of the people and crossed the border into France. Despite leaving his Kingdom, Otto refused to accept his deposition under the vain hope that his people would see the error of their ways and call for his return. Sadly for the one time Belgian King, no such call would ever happen, and with that the reign of King Otto had come to an end. Little did anyone know, the events in Belgium on the 3rd of September 1847 would spark a far greater calamity that would scar Europe for generations to come.

Next Time: The Second Belgian Revolution

[1] The Prince of Conde’s son had been killed during the Napoleonic wars leaving him without an heir of his body, as such he named his godson, Prince Henri, son of Louis-Philippe as his legal heir. Legitimists believed that Conde was contemplating fleeing to Britain alongside the Bourbons after the July Revolution, effectively disinheriting Prince Henri, the Duke of Aumale. Seeking to preserve his son’s inheritance, the Legitimists argued that King Louis-Philippe had had Conde murdered. While the case would go to trial, no incriminating evidence was discovered, and the Prince’s death was ruled a suicide in an apparent act of autoerotic asphyxiation.

[2] The manner in which cholera was spread was still relatively unknown in the 1820’s and 1830’s, leading many people to believe that it was a poison. So in effect, many Parisians believed that General Lamarque had been murdered by the July Monarchy who were jealous of their beloved general.

[3] France was forced into joining the Quadruple Alliance by a fait-accompli from the British.

[4] For reference, the population of Paris was just above 900,000 people at the time of the 1848 Revolutions.

Last edited:

Otto does have a few things going for him here that he didn't in OTL namely he had a child, albeit a girl, and he wasn't universally hated in Belgium like he was in Greece in OTL. However, he does have a few things going against him that he didn't have to deal with in OTL, so it balances out more or less.Otto-in-Belgium was as bad ITTL as Otto-in-Greece was IOTL, it seems...

The Flemish recognized that Otto was genuine in his desire to be a good king, but they also recognize that he was in over his head and somewhat incompetent to boot. So while they certainly liked him more than the Walloons did, they aren't exactly falling over themselves to make him their king again.I almost thought the Flemish would just revolt themselves and take Otto as their King and tell the Walloons to go their own way.

Things are starting to get interesting! Which I can't wait to see what the second Napoleon gets up to. Though I'm torn, because as much as I'd like to see the French do well, I'd also like to see the Dutch do well. I really would like to see the Dutch and Belgium, or parts of it anyways united and strong because that might shake up the balance of power in Europe, which would be fun.

Edit: Though I suppose things have been interesting from the beginning, but it is spreading!

Edit: Though I suppose things have been interesting from the beginning, but it is spreading!

Gian

Banned

Time to carve up Belguim between the Netherlands and France.

Or how about restoring the United Kingdom of the Netherlands?

Nah, carving it up is better, then both Walloons and Flemish can live in a country that speaks their language.Or how about restoring the United Kingdom of the Netherlands?

Otto does have a few things going for him here that he didn't in OTL namely he had a child, albeit a girl, and he wasn't universally hated in Belgium like he was in Greece in OTL. However, he does have a few things going against him that he didn't have to deal with in OTL, so it balances out more or less.

I was about to say that Otto was apparently incapable of having kids... but modern medical research has recently solved this issue while I was looking the other way as can be seen in the article (in Greek) here. https://androutsou.wordpress.com/2009/02/15/η-παρθένος-αμαλία-και-ο-ανίκανος-όθων/

Apparently Amalia was suffering from vaginal aplasia after all resulting in an inability to conceive. Well nice to know even if it took a mere one and half century from them losing the throne to determine what was going on. But for the TL that shouldn't stop Otto from having children with a different wife...

"Scar Europe for generations to come?" This sounds like Napoleonic Wars II: Coalition Boogaloo.

It may not be a Second Napoleonic Wars, but the next arc of the timeline (the appropriately named Revolutions of 1847 Arc) will have some very important developments for Europe going forward in this timeline. Napoleon II will be one and the ongoing events in the Low Countries are another, but there are several other areas which will have prominent roles in the parts to come."Scar Europe for generations to come?" This sounds like Napoleonic Wars II: Coalition Boogaloo.

Nice Job Otto, setting off the Autumn of Nations one year early.

Hey he'll be probably taking up his ministers time during the peak of the crisis with serious matters like bungles in the army need to be replaced by drums (real story during the Crimean war) while refusing the sign up everything before properly analysing it... which might take months (his Greek ministers usually waited for him to leave on travel and then gave everything to Amalia to sign in his stead. She was the reverse immediately signing anything that crossed her desk.) But he'll remember the names and status of every single Belgian civil servant to compensate.

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan League

Share: