Chapter 4 – My Lord of Spain

May – August 1381

"...This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war..."

– John of Gaunt, Shakespeare's Richard II

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, Earl of Leicester, Earl of Lancaster, Earl of Derby, Lord High Steward of England and (according to him) the rightful King of Castille. One day he was the most powerful man in England. Now, he was an exile. He had good reasons for flight. Many of his own castles had closed their gates in fear of retribution, unwilling to bring upon themselves the wrath of the mob. He was aware that his name was on their kill-list. He was also aware that his son, Henry, was down in London as it had been stormed. He felt little else but dread. With his own possessions turning him away, he had been forced to depend upon King Robert of Scotland for protection.

As the month of June wore on, the news could only get worse. The King had been taken prisoner, forced under duress to sign on the demands of upstart villeins. Even further North, where the revolt had been calmer in comparison, the peace and order had been disrupted; approved by the Archbishop of York himself, no less. England was in great pain. The Plague, the war in France, now this! Had England not suffered enough. At least Scotland was calm. He couldn't help but feel like he was failing though. He was made a solemn promise to King Edward III himself to protect the young King until he could rule himself. And then there was news of an army heading north. Now, he realised, he would have to take some action. If not stopped, who knew what this horde could do? If no one else could, he'd form an army and deal with this rabble himself. King Robert had been having similar ideas himself, and was sending out his own summons for 8,000 men. Gaunt knew he was unlikely to raise a similar number of his own, but he was willing to work with Robert. Gaunt had not come alone. Not only had he brought a small retainer, but as events continued to unfold other prominent magnates had taken up arms to crush the revolt, such as the Percy family of Northumberland.

By the 9th of July, Gaunt and Robert's force had left Scotland via Dere Street [1] headed south, aiming to secure York before heading down to Leicester - which was still holding out against the rebels - before it could fall. From there, they would smash the rebel army, free the King and liberate London. Along the way, they picked up forces loyal to Henry Percy, the Earl of Northumberland, who had also taken it upon himself to crush the rebellion and restore order to the North [2]. Gaunt's castle at Bamburgh was secured along the way as well by another force before rejoining the main army headed south. Thanks to Northumberland's effort's, the journey through Northumberland had been relatively peaceful save for a riot in Corbridge. Northumberland's case is interesting to examine. When Yorkshire's lands had been divided between the Crown, the Percy's and the Neville family, there had been competition between the Percys and the Nevilles. No doubt both families wished for greater influence over the city of York. There was also a suspicion in Northumberland's mind that the Neville family could not be trusted to restore order. The Archbishop of York, a Neville, had come to terms with the rebels and it appeared somewhat suspicious that Neville property hadn't been as badly targeted as Percy property. He was beginning to believe that the Nevilles had deliberately turned the rebels against Percy lands, such as the manor at Wressle, to gain advantage for themselves. This had caused a rift between him and the official Lord Warden of the Marches, John Neville, 3rd Baron Neville de Raby (and Archbishop Neville's brother) to open up. Whilst not official conflict yet, the two were on deteriorating terms with one another. Gaunt was frustrated by this budding feud and attempted to focus on the task at hand, restoring order to England.

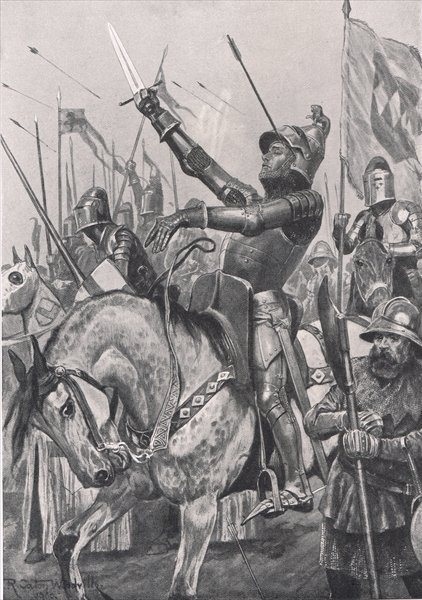

Moving on through County Durham was not so simple, the death of Bishop Thomas Hatfield [3] on the 8th of May had meant the see was vacant, kneecapping any coordinated response to the disorder, allowing various revolts to proliferate without opposition. Continuing through Dere Street, they met the makeshift army led by "warrior-priest" Alexander Miller [4] at Tow Law on the 21st of July and smashed them to pieces, killing Miller in the battle. Gaunt and Robert would continue to contain and suppress uprisings in Durham for several weeks. They got moving again at the start of August.

Tyler and his army arrived in Coventry on the 10th of July as the ordinances had called for. Much of southern and Western England was secured by the rebels, and the counties had complied with the ordinances raising men for an army. In the city, Tyler met the recently arrived delegation from Lincolnshire and Leicestershire. Led by another charismatic veteran of the French wars Geoffrey Halton, and the town's former Mayor, Robert Sutton, these rebels had already dashed Gaunt's plans by taking Leicester on the 6th when the newly-raised militia had defected and thrown the gates open, allowing Gaunt's castle there to be seized and its arms looted.

The revolt in Lincoln was similar to many northern rebellions in the summer of 1381. The region rose in revolt on the 26th of June when a crowd led by Robert Sutton and Geoffrey Halton [5], two wealthy wool merchants from the city, stormed the walls before a settlement was reached with the serving Mayor Gilbert Beesby in which the hated taxes would be rescinded and the King's charters guaranteed in exchange for Beesby keeping his office. Halton, a veteran of the French wars, would be entrusted by Sutton with the raising of volunteers for the King's (i.e. Tyler's) army. With a body of 1,000 men from the county, he headed out west. Gathering volunteers along the way, he would take Leicester on the 5th of July, dashing Gaunt's plans when the newly-raised militia defected and through open the town's gates, allowing the rebels to arm themselves from the arsenal at Gaunt's castle before burning the place as had been done to Savoy Palace his palace in Lincoln, although unlike the Savoy, Halton had taken many valuables to pay and equip his men [6].

Now at Coventry, the main commanders gathered to plan their next moves. News had reached them of the settlement in York. Whist displeased with what he saw as an unfinished job, with many of the old order retaining their posts, Tyler advised by Ufford believed he could rely on the city for loyalty. It was known that Gaunt had set out from Scotland with an army in hand, with several magnates backing him up. If they weren't careful, the rebel leaders knew that all they had achieved could be dashed, they would be executed and their dream of a free England destroyed. Tyler became nervous to reach and secure York before Gaunt did and itched to move as soon as possible. However, the army was tired after several days marching from Hertfordshire, and needed rest. Grindecobbe and Ball advised to leave on the 14th, after the Feast of St. Anthony. Reluctantly, Tyler agreed.

When the 14th came, the army set out on the long march north. They passed back through Leicester, examining the ruins of Gaunt's castle as they did, before continuing through Long Eaton, Nottingham, Sheffield, Doncaster, Tickhill and other towns besides besides finally reaching York on the 27th of July. once there, the army was allowed a good long rest. The King, the Archbishop of York, Tyler, Grindecobbe, Halton, Ufford (Lord Suffolk) and other rebel leaders met in York Cathedral, again to plan next moves. They knew Gaunt's army was heading south and that they would meet north of the city. There was definite worry in the air from some of the magnates who had thrown in their lot with the rebels, such as Ufford and Archbishop Neville. Were they now dead men walking? If it all went south, would Gaunt forgive them, or even the King? What was he thinking about all of this?

On the 31st, they all set out from the city, two days before Gaunt, Robert and their army entered the county themselves. On the 6th of August 1381, they would meet at the village of Brompton on the River Swale.

In York, the Archbishop was nervous. A settlement had been agreed and peace had been restored (mostly) to the city and its surroundings. But he couldn't help but worry about the news down south. He had heard the rumours; beheadings, burnings, execution, what of the King? And now they were headed north as well? He couldn't quite believe it. Gaunt had fled, he was in Scotland, likely raising an army of his own. He wouldn't be happy about his destroyed castles, nor would Northumberland, his former brother-in-law [7]. After the agreement in York, it appeared the rebels had taken it upon themselves not to target Neville property as they now saw him as a friend.

His brother John was with Gaunt, he was the Lord Warden of the Marches. He prayed for his brother deeply. But above all else, he prayed for England. He was a worried man, all he could do was wait. Wait and see who would reach York first. Wait and see how they would react. His worries were not relieved at first when Tyler reached York on the 27th, but when he saw that the King was with him he eased somewhat. Nervously, he agreed to meet the men the rebel leaders.

Footnotes

- [1] An old Roman road running from Newstead in southern Scotland to York.

- [2] Northumberland was appointed to restore order in northern England in OTL after Tyler was killed in London. Here, with Richard held by the rebels, he acts similarly to Bishop Despencer and takes on the rebels of his own accord.

- [3] Hatfield, a true warrior-bishop who fought at Crécy, would no doubt had suppressed such a rebellion like Despencer tried to.

- [4] Miller is fictional.

- [5] The details of the revolt in Lincoln are made up by me. Geoffrey Halton is a fictional character but Sutton and Beesby were both real individuals in Lincoln politics, with Sutton serving as Mayor in 1379 and MP from Lincoln 11 times. Here, you can imagine him (and Halton for that matter) as an ambitious man taking advantage of the circumstances.

- [6] Obviously with medieval communications being slower, Gaunt won't learn of Leicester's fall for several days.

- [7] Until 1381, the Earl of Northumberland had been married to John and Alexander Neville's sister.

Sources

www.historyofparliamentonline.org

www.historyofparliamentonline.org

From Easter to All Saints' Day, Catholic holidays celebrate the life of Christ, historical saints, and various faith-based values. Learn more about these important holidays!

nationaltoday.com

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org