Chapter 19: Come All You Bold Canadians

Come all ye bold Canadians,

I'd have you lend an ear

Unto a short ditty

Which will your spirits cheer,

Concerning an engagement

We had at Detroit town,

The pride of those Yankee boys

So bravely we took down.

The Yankees did invade us,

To kill and to destroy,

And to distress our country,

Our peace for to annoy,

Our countrymen were filled

With sorrow, grief and woe,

To think that they should fall

By such an unnatural foe.

Come all ye bold Canadians,

Enlisted in the cause,

To defend your country,

And to maintain your laws;

Being all united,

This is the song we'll sing:

Success onto Great Britain

And God save the King.

- Canadian Marching tune composed in 1812, attributed to private Cornelius Flummerfelt of the Third York Militia.

“Spring had, as is the case in our fair country, turned the roadways to quagmire and flooded the roads disturbing our ability to drill for some time, and making a great mess of the fortifications being constructed across the Province. It did though, prove quite fortuitous in deterring Yankee aggression for a time. It was of little concern to many then though, as such was the energy displayed the populace of the province that normal times seemed forgotten. Instances of devotion to Queen and country were general. Business matters were but a secondary consideration. Merchants and their clerks left their shops, students their colleges, professional men their offices, farmers and craftsmen left their fields and workshops to take up their rifles to assist in the national defence. Those who were obliged by age or infirmities to stay at home were not idle, but nobly did their part in raising funds to assist the families of those bread-winners who had gone to serve in the Volunteer battalions. All over the country large sums were raised for this purpose, and the patriotic Relief Committees were exceptionally busy attending to the proper distribution of food and supplies, both among the Volunteers and the needy families who were depending upon them.

As the politicians had been so alarmed by the events in the Caribbean with the hostile boarding of the R.M.S. Trent and the firing on of HMS Terror and the border troubles at St. Albans and Franklin, they had the foresight to call to arms the whole of our body of existing militia in November of 1861. Come 1862 they had brought yet more willing volunteers to arms, and there were some 50,000 men under arms by May.

The Province had been divided into military districts, three in Canada West and two in Canada East. In Canada West the military districts were headquartered on London, Toronto, and Kingston respectively, while in Canada East they were headquartered in Montreal and Quebec. The Province had its own military districts in each province, but the active forces were placed under the Imperial designations upon the outbreak of hostilities to avoid confusion amongst the staff. Commanding the Volunteer forces in the West were a number of respectable militia officers.

Commanding in Military District No. 1 London was Col. James Shanly, a prominent barrister who had involved himself with the militia movement since 1856 when he had organized the London Field Battery. Of good Irish stock he was an able administrator and proved himself invaluable in the opening months in handling the tasks at that most important city, having fortified Coombs Mound in the early spring.

In Military District No. 2, Toronto, of course my father was in command of the forces of the Volunteers. Such a long and prestigious militia career such as his made the choice only natural. With the organizing of our own troop of cavalry since the 1837 rebellions and my father’s service there and my uncle Richard commanding the Toronto field battery since 1858, my family was prominent in the ranks of the Volunteers of York County.

In Military District No. 3 there was a curious case of a regular officer also commanding the Volunteers. Col. Hugh P. Bourchier had a long and distinguished career in Her Majesties Imperial service. Having joined the army in 1814 he came to Canada’s shores in 1837 with the 93rd Regiment to put down the rebellion. In 1838 he became the adjutant at Fort Wellington before becoming the town major of Kingston. He helped organize the militia companies in 1855 and was a driver in the organization of the new battalions in 1861-62 and commanded Her Majesties forces at Fort Henry and Kingston. Due to these duties command of the Volunteer brigade fell to David Shaw, a solid Orangemen of good loyalist stock with experience in the militia companies since 1856.

The ardor shown by the people of the Province paid great dividends in turning out men to drill, with over 50 battalions of Volunteers armed and organized. My own specialty was the cavalry however, and our troop, the York Dragoons, or more informally Denison’s troop, was attached to the new Canadian regiment, the 1st Canadian Volunteer Dragoons[1], under Lt. Col. D’Arcy E. Boulton, a stout local businessman who had first commanded mounted troops in 1837 at 23. He fell naturally into military life and worked hard to mold us into an effective unit. We were attached to the blooming 1st Division under Major General George Napier…” Soldiering In Canada, Recollections and Experiences of Brigadier General George T. Denison III, Toronto Press 1900[2]

Lt. General Sir Henry Dundas

“Upon my assignment to Canada West I was placed under command of Lt. General Henry Dundas, a reliable old Scot who had served since 1819. He had served in Canada in 1837 putting down the rebellion there with much vigor, making his choice to command in Canada West was a natural one. With great service in India in 1847, capturing the fortress at Multan and helped smash the Sikhs at Gujrat before returning to Britain to take command in Scotland until 1860[3]. He had appealed to the Duke in order to obtain a posting in Canada and so came to command in Canada West. I was placed on his staff alongside other such capable officers as Patrick MacDougall the chief of the staff, John Wayland the chief aide-de-camp, and Richard Mountain, who was drilling the militia artillery.

He had established his headquarters in the Queens Hotel of Toronto where he maintained easy communications with all points on the frontier. We were also kept in contact with our forces afloat through the person of Captain John Bythesea, VC. A regular war hero who had so ably demonstrated his courage in the Baltic under Dundas, the brother of our General Dundas. I daresay had it not been for him the forces available to us on Lake Ontario would have suffered much for it.

Our forces in the field were under the command of perhaps the most mismatched pair of officers to have ever served together. One of course was Randall Rumley who had thirty years of experience under his belt. Most of his service had been with the Rifles and he was an infantry training specialist by reputation, something sorely needed by the Canadians in those early years, but had not seen any active service in the field prior to 1862.

Commanding the division which was based out of London however was the newly minted Major General George T. C. Napier. Useless for any military purpose he was not considered a shining light by his peers. In that case my orders both from headquarters and Dundas specified I should “coach” him and prevent him from doing anything too foolish. Indeed he seemed delighted to have by him someone whose advice he could follow. Though in private a charming man, he was at all times useless as a military commander, and yet he was a fair specimen of the men then usually selected for military commands.

After a brief stay in Toronto where I familiarized myself with the local organization of the militias and appointed a man to act in my place on the staff I went by train to London with a troop of volunteers for company.

That part of the province which London is situated in is picturesque. Good green rolling country, crisscrossed by springs and rivers it is rich in agriculture with numerous small farms and orchards along the roads. The industrious nature of the Anglo-Saxon race is much in evidence with mills all along the rivers and many fine shops worked by the good peoples of the province. The more entrepreneurial nature of an Englishman freed from the base nature of French priestcraft thrived amongst the populace, which was well evidenced by the numerous towns and cities, in stark contrast to the rural and dour nature of the French in Quebec.

London is the local seat of government in Middlesex County, an industrious city of 11,000 in those days. Its great importance was as a hub of rail travel for the Grand Trunk railroad leading to Detroit and the Great Western railroad connecting Sarnia to Hamilton, and numerous gravelled roads moving out from the city like spokes on a wheel besides. As such its control made an advance by the enemies from the Detroit frontier to the interior impossible without being contested, and left any advance up the Niagara frontier open from the flank, increasing the hazards any enemy force operating alone from either side might face.

My first duty upon reaching London was the surveillance of our position there. Unfortunately it was an unenviable position for even a well-trained army to find itself in possession of. The position was separated by the Thames River, at that point flooded, and though there was high ground which protected the city at Coombs Mound and Komoka, these positions could not support one another in case of battle. Though they shielded the roads south and west from Chatham and north and west from Windsor, they were not suitable for the covering of the town, and despite my protests Napier insisted on selecting these positions to fight the coming battle at…” – The Story of a Soldiers Life, Volume II, Field-Marshal Viscount Garnet Wolseley, Westminster 1903[4]

Major General George Napier

“By the spring of 1862 armies north and south of the border had been gathering for war. To the south, a large force had been gathered from all the armies previously turned against the Confederate forces in the West. Now though they stood ready in two armies facing the British in Canada.

The newly created Department of the Lakes encompassed a broad swathe of the border from Michigan to the borders of Vermont. It was this great area which now lay under the responsibility of Major General Henry Halleck. Balding with gray mutton-chop side whiskers he looked considerably older in his years than he was, and had earned the nickname “Old Brains” amongst his fellow officers. His service in Mexico and his writings thereafter had distinguished him as a great military theorist amongst his peers, and his choice to command that vast front had been seen as obvious. He had gathered a creditable staff, both from his command in the West and from men who had come to the colors once again. These included his chief of staff Col. Carlos Waite, a long time veteran of 1812, and his chief engineer 53 year old Col. George Callum whose years of experience constructing bridges and fortifications would prove invaluable in the coming campaign.

Commanding the newly christened “Army of the Niagara” or I Corps, Department of the Lakes, was Major General Charles F. Smith. The 55 year old Smith was a tall, handsome, long time service veteran who had graduated West Point in 1825 with distinction and had served as an instructor in that academy only four years after graduating. Serving in the artillery and infantry, he was brevetted three times for bravery in Mexico. He participated in military boards to devise new artillery mounts, and served in the Red River expedition of 1856 and the abortive Utah War of 1859-1860. Before the outbreak of the civil war he found himself briefly commanding the department of Maryland before being dispatched by his old chief, General Scott, to Kentucky where he displayed ample ability in preparing that state for war. He served under Grant at the battle of Fort Donelson, and was seen as instrumental in overrunning the Confederate entrenchments which lead to the surrender of the garrison. His choice to command the force then assembling to invade Canada was thus a natural one.

Major General Charles F. Smith

He was at the head of an army, which though not entirely green like his Canadian counterparts, was one with mixed abilities. Fractious attitudes reigned between the officers, and many men had been pilfered from three different armies in the West, making their drill and training together from March to May of 1862 crucial in their early time in the field.

Under him were four divisions worth of troops, infantry, artillery, cavalry, and engineers, totalling over 30,000 men. Each division commanded by men who had been blooded in the Western theater.

The first division was under the command of Brigadier General John McArthur, a Scottish immigrant to the United States he had been appointed colonel of the 12th Illinois Infantry and rose rapidly in the ranks to Brigadier General of Volunteers, leading a brigade with distinction at Donelson. His foreign mannerisms well on display, he eccentrically adopted the Scottish hat for himself and his men followed in that, earning his force the nickname of the “Scottish Division” after its commanding officer. The second division was under the command of Brigadier General Jacob Ammen, who had taken command for William Nelson who had returned to naval service on Lake Ontario. Ammen was a graduate of West Point in 1831 with honors and specializing in artillery and mathematics, he had retired to civilian life in 1837 to teach, but rejoined upon the outbreak of war and first seen action at Cheat Mountain in 1861. In the third division command rested upon the shoulders of Brigadier Benjamin Prentiss, a Virginian born loyalist to the Union he had served previously in the Mexican War and now commanded a division against the British. Finally the fourth division rested in the hands of Brigadier John M. Palmer. The 44 year old politician had never served in uniform before, but he made up for that shortcoming with remarkable determination and forthright character. Speaking his mind and riding his men hard he had worked his way to commanding a division without seeing a single full scale battle.

From left to right: McArthur, Ammen, Prentiss, Palmer

These forces formed part of a broader stratagem by the Union in the spring of 1862. Lincoln and his generals knew that it would be unacceptable for the Union to merely sit on the defensive, with that came down the strategy of 1862. The cabinet knew that it needed to protect its coasts while also delivering a blow to the rebellion, but it needed a way to damage Britain, if not materially at least in prestige to force her to the negotiating table. Thus the obvious strategy of targeting Canada came about, and as one military theorist who served in that contest would later say: “There with Kingston and Montreal, by their position and intrinsic advantages, rested the communication of all Canada, along and above the St. Lawrence, with the Sea Power of Great Britain. Then, as in the conflict of 1812, there was the direction for offensive operations.” Such stratagems rested perfectly with the Jominian view of war as espoused by Halleck.

So he directed a long flanking movement with Smith’s army, designed to stretch the resources of British and Canadians thin, and to strike at the vital positions necessary to command the St. Lawrence. Palmer’s division would be sent across the Detroit frontier to push the British, while Ammen’s division would cross at Prescott and take Fort Wellington. Meanwhile, the major invasion force, directly under Smith’s command consisting of Prentiss and McArthur’s divisions would cross the Niagara frontier with the goal of pushing the British forces back to Kingston where they could be trapped and compelled to surrender.

However, despite the knowledge that speed was essential, and timing supremely important, Halleck dithered until mid-May, fixating a ensuring that each wing of his army be prepared to march at the exact same time to pin the British in place. When the armies finally did begin advancing on the morning of May 17th, the British were well prepared to meet them.

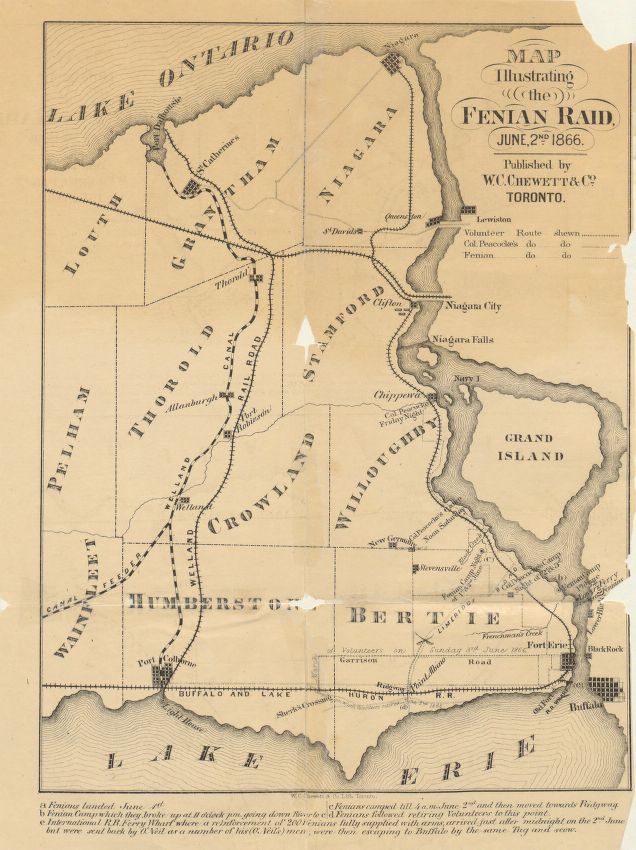

The invasion began in the early hours of the morning, just prior to dawn. On the Niagara frontier the British brigade under Col. James T. Mauleverer, a veteran of frontier fighting in India and Africa with service in the Crimean War at the Alma and Inkermen, led a bag of the best troops the Canadian Volunteers had to offer. Comprising of the Volunteer battalions from Toronto and York county, most of these men had been drilling since November of the previous year, and each unit had an attached wing of regular troops to act as stiffeners in the defence. The 2nd Battalion of Volunteer Infantry (the Queens Own) under Lt. Col. William Smith Durie, a long time militia officer, had been formed in 1860 and as such had been called out in November in response to the border raids. The 10th Battalion of Volunteer infantry was younger, having been formed provisionally in November and established officially at the beginning of December under Lt. Col. Frederic Cumberland. Finally there was the 12th Battalion of Volunteers, also formed in December under Lt. Col John Worthington. They had been drilling alongside the 30th Foot since December, even as a brigade, and thus were well prepared for the opening battles. The addition of a “wing” of soldiers from the 30th meant each battalion was over 1000 men strong.

Scattered from Niagara to Chippewa, and Fort Erie, they occupied temporary fortifications, not meant to engage in direct battle, but slow the invaders and harass their flanks. This would be done with the support of the 1st Canada Dragoons under Lt. Col. Boulton who had attached a troop to each battalion, and two more at Mauleverers headquarters at Thorold, putting fully half the units’ strength on the peninsula.

Diversionary landings were made at Queenston and Chippewa by McArthur’s division, but the full might of Prentiss’s division and a detached brigade from McArthur’s landed at Fort Erie on the morning the 17th. Crossing the lake from Buffalo under the guns of the “Lake Erie Squadron” under Commodore Silas Stringham in the USS Michigan, the only actual warship on the Lakes, a horde of steamers, tugs, and barges deposited the American troops on the Canadian shore. The invasion alarm flashed out across the country by telegram, and the forces which had been readying for war since November began embarking for positions chosen in the previous months…

…On the Detroit frontier, only a single division had been tasked with making a sweeping attack from Windsor to Sarnia. Palmer’s Division, supported by a single brigade of Michigan militia and Home Guards, crossed the frontier. Palmer and his main force crossed from Detroit, while a reinforced brigade crossed at Sarnia and advanced towards Komoka. Palmer and his attached force laid siege to the newly reoccupied Fort Malden. After two days, with just enough resistance to satisfy honor, the single Royal Canadian Rifle company and attached militia gunners under Captain Alexander Gibson surrendered, hauling down the Union Jack to see the Stars and Stripes raised above the old fort made it the first post in British North America to surrender to an enemy since 1812.

Palmer’s force was, after detaching its militia element to act as the garrison on the Detroit frontier, totalling 7,500 men and 18 guns. Comprised thusly:

4th Division, I Corps, Department of the Lakes: BG John M. Palmer commanding

1st Brigade (Col. James R. Slack): 34th Indiana, 47th Indiana, 43rd Indiana

2nd Brigade: (Col. Graham N. Fitch) 46th Indiana, 22nd Missouri, 64th Illinois “Yates Sharpshooters”

Division Artillery: 2nd Battery Iowa Artillery (Cpt. Nelson T. Spoor), 7th Battery, Wisconsin Artillery: (Cpt. Richard R. Griffiths), Battery C, 1st Michigan Artillery (Cpt A. W. Dees)

7th Illinois Cavalry (Col. William P. Kellog)

Palmer’s forces advanced east towards London, skirmishing with Canadian militia the whole way. The militia troops fell back towards London, aiming only to slow the invaders down. As the telegraph wires flashed out the invasion signal, troops began advancing to their positions.

Major General Napier had command of the 2nd Division, Upper Canada Field Force, which had been tasked with defending London and stopping any American advance inland. His force, totalling some 8,800 men and 18 guns was arranged like so:

2nd Division, Upper Canada Field Force: MG George T. Napier Commanding

Division Troops: 2nd Canadian Field Brigade (Maj. John Peters), 3rd Canadian Volunteer Dragoons (Maj. Norman T. Macleod) 5cos

1st Brigade, (BG. Charles Fordyce) 2nd Royal Canadian Rifles, 22nd Battalion “Oxford Rifles”, 26th “Middlesex” Battalion Volunteer Rifles,

2nd Brigade (Bvt. Col. Edward Newdigate), 23rd “Essex” Battalion of Infantry, 24th “Kent Battalion of Infantry, 25th “Elgin” Battalion

3rd Brigade (Bvt. Col. Henry R. Brown), 31st “Grey” Battalion of Infantry, 32nd Battalion of Infantry, 33rd Battalion of Infantry

Support Troops: London Garrison, Col. James Shanley, 56th Battalion of Infantry, London company of Foot Artillery

Despite being a relatively flat piece of country, the cavalry for the division was lacking. Most of the battalions had only been raised relatively recently in December and January, and had drilled sporadically with the Royal Canadian Rifles. Their artillery, under the newly organized “2nd Canadian Field Brigade” had been formed from the London Field Battery, and the companies of foot artillery from Goderich and London. Though the London field battery had received a battery of modern Armstrong 12pdr field guns, the two other batteries were armed with cast off militia 9pdr field guns and 12pdr howitzers.

The second brigade, under Newdigate, was comprised mainly of men whose homes were in the direct path of the American invasion. As such they were the first to draw blood when Palmer crossed the border. They withdrew, and delayed this force as long as they could. Palmer worked to re-establish communications with his 1st Brigade under Slack, but his own deficiency in cavalry meant he was mostly out of contact with his second brigade. His force though, advanced along Egremont Road, until they arrived just outside the village of Komoka where Napier’s 3rd Brigade under Brown was established. He would wait for three days before he received word from Slack, but when he did the battle was joined on June 2nd…” – For No Want of Courage: The Upper Canada Campaign, Col. John Stacey (ret.), Royal Military College, 1966

-----

1] This is a completely original unit created by the British to mould the Volunteer cavalry into a more cohesive and effective fighting unit. I created it by combining the various volunteer cavalry companies in Canada West to create roughly regiment sized cavalry squadrons to attach to each Volunteer division.

2] Like other period sources some of this is word for word from Mr. Denison himself, and others bits of my own creation for the narrative.

3] Sharp eyed readers might remember him from last time.

4] Again bits of this are Wolseley’s writings and bits are entirely fictional.

5] Yeah it's the map from 1866, but sue me!