I hope there is greater reshuffling if Union Officers TTL, with the presence of the General Staff and the gravity of the situation. Although it seems grumblings about the way Washington is handling the war has already started.

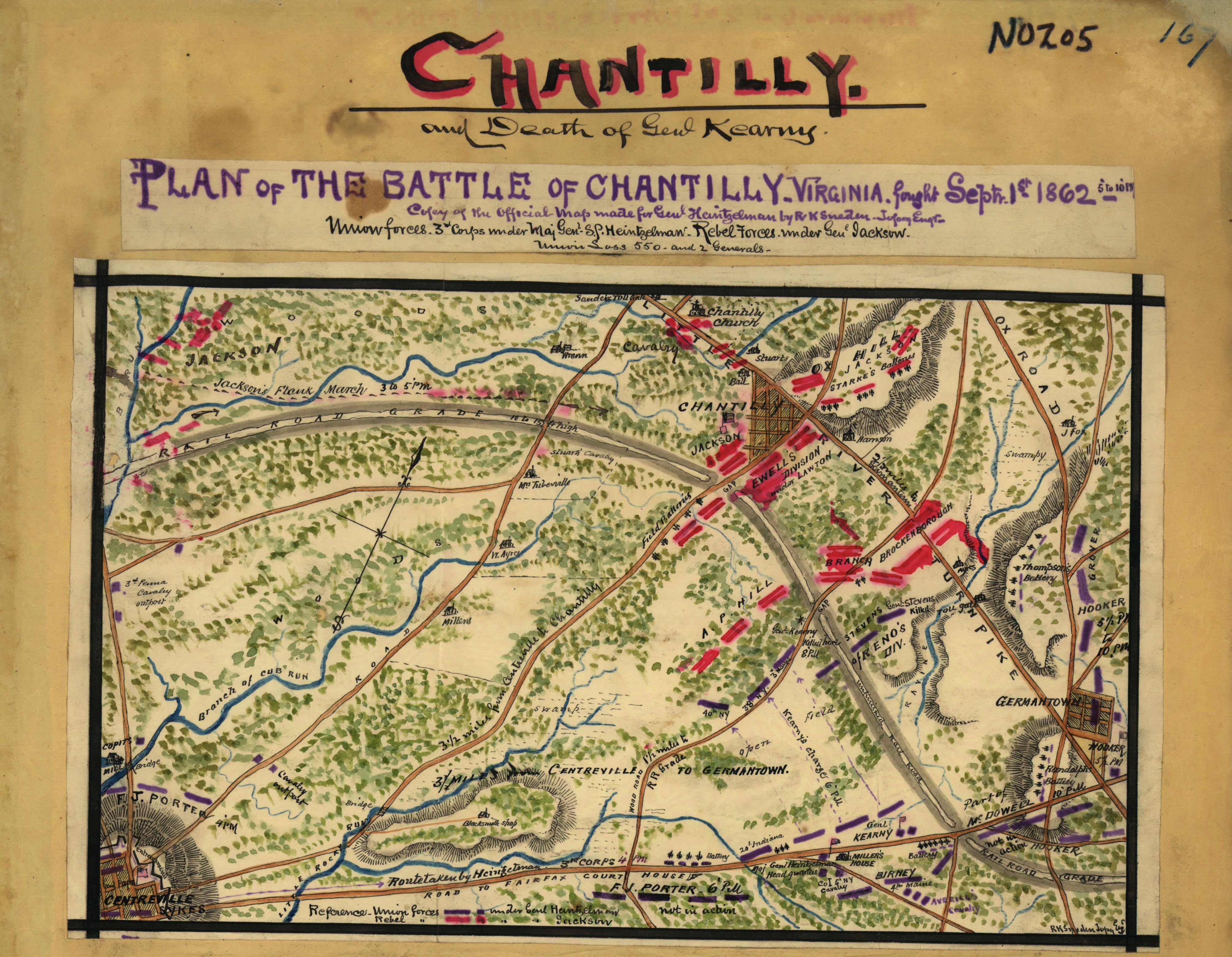

In 1862 the Union is still undergoing its "teething" phase with the army. Men have been shuffled around where they've been needed and they've been appointed as needed based on merit or reputation and seniority. There isn't yet a general staff for the Union and the "Board of National Defense" is more of an advisory body meant to formulate plans and strategy (think of a very rough prototype of the Joint Chiefs) who offer advice to the now General in Chief Dix, who in turn advises Stanton and in his stead gives orders to the various Department commanders across the continent.

Though if things don't go well into 1863, there might be some shuffling upcoming.

There's been grumbling in the handling of the war, and alas it shall continue (as the Democrats will grumble even if things are going well) and with the Emancipation Proclamation now issued, its going to give them more things to grumble about.

However, it has a very nice side effect of providing some material advantages and clearing up the tricky issue of contrabands. There's also the not so insignificant fact that those contrabands can now attempt to enlist if they so choose.