Chapter 94: Colonial Matters

Chapter 94: Colonial Matters

“While it is often considered that Canada was the only British colony at risk from the United States, many of Britain’s far flung outposts also lived in fear of retaliation from, if not the armies of America, her commerce raiders.

This was the primary concern of the six different Australian colonies of Britain. Though Britain maintained units of Royal Artillery at important ports and had companies of infantry scattered across the continent, these were insufficient to do more than deal with occasional civil unrest and the odd skirmish with the Aboriginal peoples. The threat, or at least fear of, an American attack on Australian coasts prompted a flurry of calls for more forces from Britain. However, the colonial governors were all rebuffed by London who informed them that forces were already destined for North America or China and nothing could be spared beyond artillery detachments and guns.

While there had been some organization and spending in response to the Crimean War, the various responsible governments in the colonies were passing motions for an expansion of Volunteer formations. Only the memory of the Eureka Stockade years prior prevented the adoption of conscription. Instead, they pushed for the arming of “the proper classes” (Lord Lisgar) to discourage unrest and to properly protect the colony in case of attack. New South Wales managed to raise a force of 4,000 Volunteers by the winter of 1863. However, over three quarters of those would eventually be tempted away by land deals during the New Zealand war in 1864 leaving the defence of the colony in doubt during 1865. It was this which prompted discussions with Victoria, who had maintained a solid core of urban Volunteers for a small semi-professional force of 1,500 about matters of a coordinated defence policy. However, it also created conversations between the two colonies regarding whether some sort of united front might be presented outside the military sphere…

In New Zealand, while the threat of American raiders was assessed as real, there was a sense of security from the Royal Navy, and the brigade of troops dispatched to help police the troublesome Maori King Movement in the Waikato. The real threat in the minds of most New Zealanders was the Maori…

From a naval perspective Seymour’s Australian Station was charged with policing the waters around Australasia. Despite some raids, and one significant action with the converted American mail steamer California, the station was largely quiet throughout the war. Maitland chiefly concerned himself with commerce protection and convoying men to New Zealand when the outbreak of war there came…

Only in China, oddly, did any real conflict occur between forces of either side. While the United States had withdrawn its forces from overseas at the outbreak of the Civil War, they had left a token presence in Asian waters to show the flag and enforce American policy. By the outbreak of war in February 1862 the American presence consisted solely of the gunboat Saginaw under James F. Schenck laid up at Whampoa. His opponent, Admiral James Hope, had a much more significant command to draw upon.

Upon the confirmation of the outbreak of war in March, Hope acted quickly to seize American ships and property at Hong Kong and Shanghai. Schenck and many of his subordinates were taken into custody. Despite blistering complaints to the nominal Qing overlords of Shanghai, the opinion of the local merchants, and far away Beijing, was that it was a foreign problem for foreigners. Certainly the reports of barbarians fighting barbarians did not cause Qing courtiers to lose a night of sleep.

Brief fights were experienced in mid-March between some Americans and then British troops, largely tavern brawls. By and large however, the conflict was contained to confiscations and occasional disputes between British and American consuls over who owned what. The dispatch of the 99th Regiment of Foot caused much comment, but played little into the events at Hong Kong. The Taiping proved more easy to repel than expected, and the loss of the 99th made no impact on the eventual campaigns.” - The Third Anglo-American War Abroad, Jonathan Hemsworth, Glasgow Press, 1981

An Australian Volunteer Gun Battery, 1869

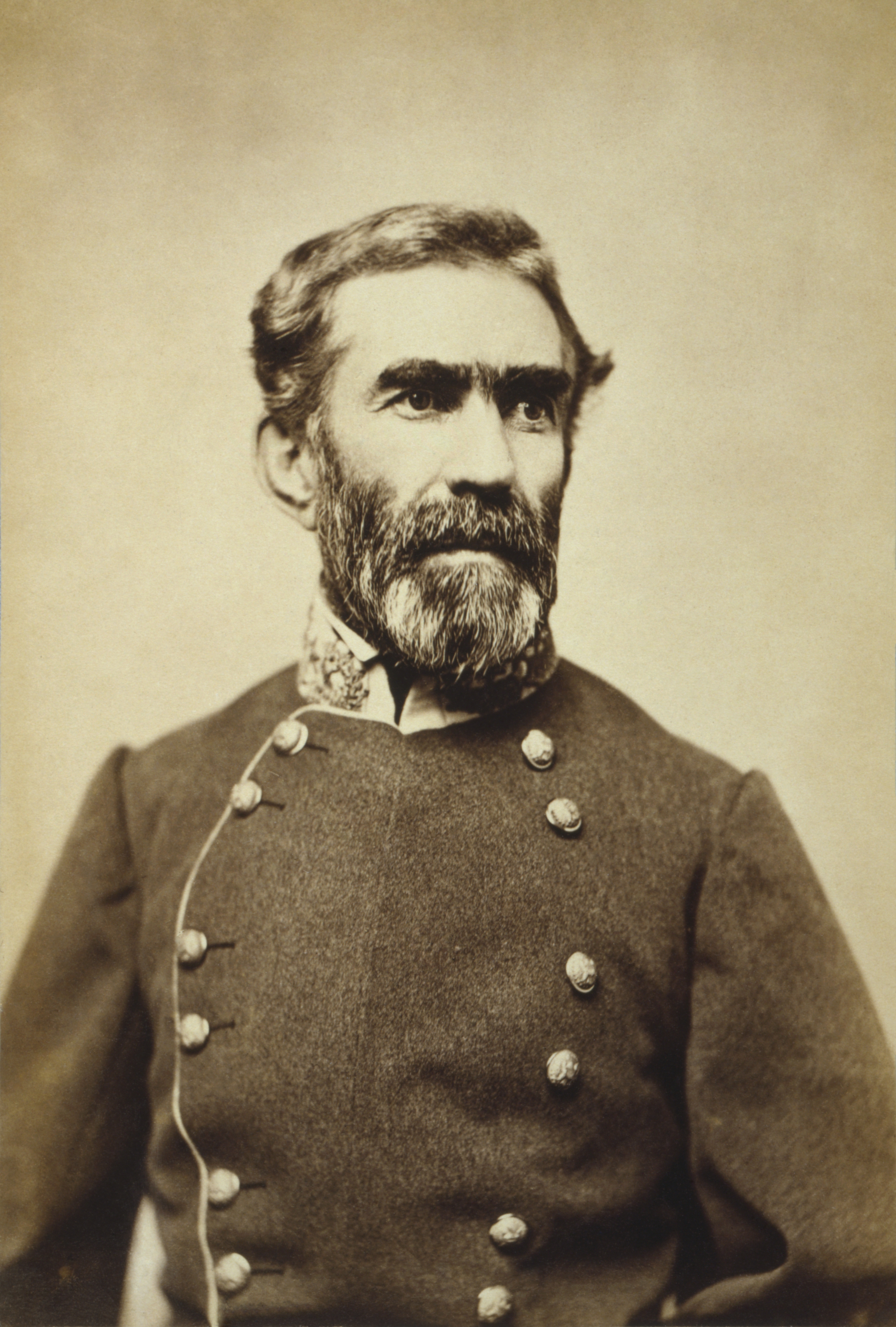

“Though it was a diminished fleet and force which eventually again settled at Honolulu, King Kamehameha would personally take the time to interview the British officers who landed. Inviting them to the ʻIolani Palace, he would speak with British officers regarding events in the United States.

Was it true, the King asked, that Britain had humbled the United States at home? He was told this was confirmed. Was it also true that they had destroyed American power in the Pacific. Proudly the Royal Navy officers confirmed that, apart from American raiders, they had cleared the Pacific of American warships leaving “nothing greater than a clipper waving the American flag from China to California” he was told.

The matter deeply intrigued the King, and he began taking many lunches with British Consul William Synge who he knew well, as he had stood in as Queen Victoria’s representative at the now six year old Prince Albert’s christening. There was, as usual, talk of trade, the improvement of the Anglican Church on the islands, and at last the might of the Royal Navy. The King was interested in whether it could protect his home from encroachment of a foreign power. Synge, in perhaps a bout of patriotic overstatement proclaimed “Your Majesty, no ship could sail in these waters if Her Majesty’s Navy did not wish it. Brittania rules the waves of all the Earth.”

While perhaps not imparting the meaning in quite the way he thought, Synge did give the King pause. He had hoped to leverage British support economically as a mean to ward off American political and economic encroachment. But perhaps he could do more…” - The House of Kamehameha, Brandon Somers, Oxford Press, 1987

Diplomat William Synge may have had an outsized effect on Hawaiian history

Last edited: